Asylum’s Woes and Triumphs

Indonesian immigrants’ battle for a new home

by Alessa Erawan

Former asylum-seekers from Indonesia grapple with resettlement as they face a loss of economic opportunities, prolonged struggles with the US immigration system, and difficulties in rebuilding their community.

New York, New York — Anastasia Dewi Tjahjadi and Realino Adi Wijaya are forever grateful. Tjahjadi, for the refuge she and her family found in New York City when the collapse of Indonesia’s economy in 1998, forced her to leave her home country; and Wijaya, for the asylum the United States provided when Indonesia did nothing to counter vicious attacks on its ethnic Chinese citizens. Tjahadi’s gratitude has withstood all the early hardships of her transition, even the overly cramped apartment in Queens and the decade-long legal battles she had to fight. For his part, Wijaya stayed positive throughout weeks of ICE detention after he had been in the United States for less than a year. Most of all, both are grateful to be with their families in the United States and to be thriving.

Their stories echo those of many immigrant groups in the United States: religious or other minorities who have fled their home countries to escape persecution that their governments refused to tame or, even worse, support. For many ethnic Chinese Indonesians who fled in the years following 1998, resettlement has meant a loss of economic opportunity, prolonged struggle to secure US legal status, and the difficulties of rebuilding community as they adjust to a distant new homeland, where prejudice against foreigners is prevalent, made worse by the ignorant racist remarks they’ve been subjected to because of COVID-19. More often than not, they find they have to rely on each other than on their new government.

![]()

Before the events of 1998, life for Tjahjadi and her husband was good, a middle class couple with a driver and a maid, a common household makeup in Indonesia. Tjahjadi worked as a manager at an insurance company and her husband held a high position in the Indonesian office of a Taiwanese firm. His proficiency in the Chinese language was an asset his bosses rewarded. So when Tjahjadi finally made her way to New York City in 1999, the three-bedroom apartment in the Corona neighborhood of Queens he found for them to share with seven other people came as something of a shock. I thought it was going to be something like Melrose Place, the TV show, with the mansions and the pools and the cars, she said, Not this small room that we had to share with so many other people.

What forced them to flee in the spring of 1998 actually began the year before when a catastrophic financial crisis hit Asia, with Indonesia among the most affected countries. By January 1998, prices for basic food staples had increased by 80 percent—a kilogram of rice cost 2,800 Rupiah, more than double what it cost a year earlier. By the end of the year, World Bank official reports said that 40 percent of the population had fallen below the poverty line.

Locals looting shops amidst the protests in May 1998 (photo by Choo Youn-Kong for Getty Images)

When the crisis first began, protests erupted with the demands for President Suharto, the dictator who had reigned for 32 years, to help the people or step down. What started out as vocal protests against Suharto morphed into violence. On May 12, the military opened fire on student protesters who staged a sit-in near the parliamentary building, killing four.

For nine-year-old Lusiana Hadi, now an accountant in the San Francisco Bay area, May 12, 1998, was a big day. Her school in Jakarta had let out early and upon seeing a commotion near her house – which turned out to be protesters looting Chinese-owned shops – Hadi ran home to safety. She recalls her mother packing clothes for her and telling her she would stay with a family friend that night. “If anything happened, I had to climb up to the roof and hide. We heard about many young girls who were raped during the mob and so my mother said, ‘Do not wait for us – whatever you do, run as far as you can and save yourself,’” she said.

To Tjahjadi, moving became inevitable once her source of income and safety were stripped away. Seamlessly, almost by rote, she recounted the events of May 14, 1998. My father-in-law owned a paraffin lamp shop at Pasar Pagi, the marketplace in Jakarta’s own Chinatown, she said. My husband’s family was quite comfortable economically, so they had a driver, which was good because his father was getting old, like in his late 60s. On the day of the Trisakti demonstrations – the university near the parliamentary building that got shot at – everyone at the market wanted to close early. My husband wanted to make sure his dad was okay, so he picked him up himself at around 3 pm, so he wouldn’t be stuck in traffic.

But soon, they entered the area near Gambir train station, where a mob awaited. My husband’s car was this wagon-style Toyota with tinted windows. The mob just started randomly smashing cars – and they did it to my husband’s car. With the protection of the window gone, the mob could clearly see there were two Chinese men. The mob pulled them out of the car, Tjahjadi said, looking down at her hands and blinking fast. My husband had cuts across his arms and they took away their wallets. They made it out there alive, though.

“The mob pulled them out of the car. My husband had cuts across his arms and they took away their wallets. They made it out of there alive, though.”

Although Jemma Purdey, a research fellow at Monash University’s Australia-Indonesia Centre, points out there is no firm consensus on the actual number of victims, in her book, Anti-Chinese Violence in Indonesia, 1996-1999, she estimates that about 1,000 people died in the riots and more than 80 women and children were raped. Another report in an Australian journal found that more than $250 million had been lost. Most targets were the ethnic Chinese, who were also Christians, and who make up less than 1 percent of the population of what is the largest Muslim country in the world. (However, this number is almost certainly an underestimate of the actual population as it relies on “self-identification”). The turmoil, known as Tragedi 98, sent somewhere between 10,000 and 150,000 Chinese-Indonesians to Singapore or Australia, or in some cases, like Tjahjadi, Wijaya, and Hadi, to the United States.

These anti-Chinese sentiments are nothing new to the country. Purdey’s book explains that under Indonesia’s three centuries of colonization by the Dutch, the Chinese became the middlemen between the Dutch and pribumi – a term used to describe native Indonesians – as tax and revenue collectors. (The 1740 Batavia massacre, which left at least 10,000 ethnic Chinese dead, was one of the first signs of targeted violence against this group.) Citizenship became a major issue in 1945 when Indonesia gained independence. The new government adopted the principle of jus soli, under which citizenship is only conferred by the country of origin. Meanwhile, China adopted jus sanguinis, where the citizenship of the parents determines a person’s citizenship. Thus, Indonesian-born Chinese people had dual citizenships, which made other Indonesians question if they had divided loyalty.

In 1965, a failed coup attempt by the military led to, as a secret report by the CIA states, “one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century,” comparable to the Soviet purges of the 1930s, the Nazi mass murders during the Second World War, and the Maoist bloodbath of the early 1950s. The large-scale killings and civil unrest that lasted less than a year began as an anti-communist purge, but soon targeted just about anyone, including ethnic Chinese, alleged leftists, artists, politicians, and writers. Between 500,000 and two or three million were killed, though no exact number was ever obtained by the government or any external task forces. In 2016, the International People’s Tribunal in the Hague, presided over by seven international judges, found the state of Indonesia directly responsible for the events and guilty of crimes against humanity. The Tribunal classified the massacre as a genocide. No one, however, has been held accountable for this.

In its aftermath, Suharto came to power and implemented sweeping regulations that outright banned the expression of Chinese identity. Tom Pepinsky, a political scientist who teaches Southeast Asian politics at Cornell University, said Suharto’s policy obliged the ethnic Chinese to change their names so that they sounded more Indonesian. Suharto also prohibited the use of Mandarin language in public, closed down Chinese language schools, and forced adherents of Taoism and Confucianism to leave their religion for one of the five faiths Indonesia recognized.

At the same time, Suharto understood the entrepreneurial spirit of this community and recognized its potential as a force for economic improvement. He used the ethnic Chinese Indonesians to push his economic development programs, allowing him to tighten his grip on the government and people. An article by an Indonesian scholar at Monash notes the “paradoxical policy of privileging the Chinese business communities in expanding the nation’s economy, and reducing the entire ethnic minority to near pariah status in all social spheres.” The Chinese business elite thrived under Suharto, even as the government deprived them of civil rights.

The Chinese-Indonesian population at that time was only about 0.9 percent – a figure that an official UK government agency said was underreported, as it relied on self-identification and “many Chinese would undoubtedly have been reluctant to identify themselves ethnically.” But the most elite of the community amassed about three-quarters of the country’s corporate wealth. That also meant they needed Suharto to protect them. Pepinsky said Suharto was happy to oblige. Smaller shop owners also got protection by paying off local military officials or native business partners. This system was then used against the community, as Suharto’s regime spread rumors of corruption, collusion, and nepotism in Chinese-Indonesians’ business practices.

Researchers Siew-Min Sai and Chang-Yau Hoon observe that as the “middleman minority,” the Chinese Indonesian community acted as a buffer between the elite and the public in commerce and in times of social hostility. The elite, as Suharto did, used them as scapegoats to deflect aggression from themselves, while for the masses who needed to vent frustration at the state, the middleman became a useful target. William Frederik Wertheim, a sociologist at the University of Amsterdam, compares ethnic Chinese groups in Southeast Asia with the Jews in Europe before World War II, drawing parallels between the two as trading classes and persecuted minorities. However, Wertheim, a Marxist, attributes much of the discontent among the pribumi to class rather than race.

Realino Wijaya (photo by Wijaya)

Both class and race contentions have contributed to disputes that often turned violent. Wijaya recalled that as a teenager, just 12 or 13, turning off a main road on foot in his hometown Surabaya, he felt a motorbike was following him so he quickened his pace. The motorcycle sped up, caught up to Wijaya. Two men got off the bike and pinned him to the side of a building. They said, “You’re Chinese.” His heart raced as he braced for what was to come. One of the men held his face up, took a puff of his cigarette and stuck the butt of it under his left eye. They then let him go and he ran home, wincing and crying as the cigarette burned his skin.

![]()

Anyone who looked Chinese could be a target. Tjahjadi recalled a story her parents told her of a middle-class family in Jakarta who hid in their house as a mob forced its way in. They ransacked the place and a few of them attacked the family’s teenage daughter. Her father retaliated as they raped her and one of the assailants grabbed an empty glass bottle, broke the end of it, and shoved the rest into her. When her parents took her to a local hospital, the doctors informed them that they did not have the equipment to help her and referred her to a hospital in Singapore. By then, tiny glass shards had infiltrated her blood vessels and traveled to her heart. She died soon after.

The office of Tjahjadi’s husband shut down within 48 hours of the violent outbreak. The city went dead. No one dared to stay outside after sunset and women became fearful of leaving their houses alone at any time. Tjahjadi’s father-in-law refused to go to his shop for six months, and even afterwards, only wanted to stay for about an hour and left the rest of the business to his helpers. Tjahjadi soon lost her job, too, as the country’s economy plunged further.

In January 1999, she ran into a friend who said the money in the United States was good. Tjahjadi proposed the idea to her husband, and although he was reluctant at first, he agreed. They applied for tourist visas, unaware of the legal issues this mode of entry would cause if they overstayed the allotted time. They were eager to earn money in the United States, especially with the exchange rate between Indonesian rupiah and US dollar at the time, and use it as capital to start a business back in Indonesia.

Tjahjadi’s husband left ahead of her—she had to take care of her parents—and he first ended up in Colorado. At the suggestion of a couple other Indonesians who had migrated to the United States, he moved to New York City where, he said, the money was better. A couple of months later, Tjahjadi followed, arriving in New York on Sept. 21, 1999. An agency in Chinatown helped them both get jobs.

My first job was at a laundromat, she said. I made $5.50 an hour but could only stay there for one month because the boss was horrible. Then I moved to a dry cleaning place and worked for $6.25 an hour. Her husband became a waiter at a restaurant in Queens.

Much like Tjahjadi, Wijaya, who did not arrive until 2003, decided to move because economic opportunities had become so scarce in Indonesia, especially for someone who looked so stereotypically Chinese. When he first arrived, he worked various jobs at restaurants—as a runner, busboy, and waiter. Eventually, he worked as a food runner at a Japanese fusion restaurant in New Jersey, but his time there was cut short as he got sent to ICE detention. After his release, he worked at another fusion restaurant in New Jersey for a year. Now, he drives a yellow cab and does some small-time investing. He even has a book on Amazon about investments. His wife, whom he met through the Indonesian church, is a part-time waitress in Bronxville, working two days a week, five hours each day. Most of her time, however, she spends raising their two young children.

Tjahjadi realized early on the hardships and the hard work that would be needed to build a career in this new country. I’m an unskilled worker, she said, I can only do hard labor. For most new Indonesian immigrants in New York City, the food business provides the most accessible opportunity, despite its usual limitations of a minimum wage base and dependence on tips. Tjahjadi, with her entrepreneurial mindset—a running joke that the ethnic Chinese always think of everything as a business— started various food enterprises of her own, all centered on the unique flavors and spices of Indonesian cuisine. She was never formally trained in the culinary arts (although she has said she wants to take up courses like baking at the Culinary Institute of America) and she was never a cook back home, but in New York’s lack of authentic Indonesian fare, she saw opportunity.

In 2005, Tjahjadi and a couple of friends rented a two-story community events space in front of the Queens Library in Elmhurst. The space was not zoned for commercial use but Tjahjadi found a loophole: they would rent out the first floor for community events and use the second floor as a kind of makeshift store/restaurant. They called their shop Indonesian Community Center (ICC). Business was good, but in 2007, they closed down. The next year, Tjahjadi and some business partners, who met each other through the Bethel International Church in Elmhurst, decided to open another store. Philadelphia was known for having several Indonesian grocery stores, where pre-packed food is sold to provide all sorts of culinary experiences to the customers. New York had nothing similar. Along with two other friends, she rented a spot not far from her home and now runs Indo Java.

At the same time, she began thinking up ideas for how she could earn more. In 2009, Tjahjadi and these same business partners opened a new restaurant with a similar concept to ICC not far from the old store’s location. This one was called Java Village. Tjahjadi was in charge of the cooking and quality control. That gave her two going businesses: one that sold everything like instant noodles, home-made traditional sweets like Terang Bulan, boxed teas, and even Indonesian medicine; and another where she was the main cook.

Tjahjadi in Warung Selasa (photo by Jessica Lehrman for The New York Times)

As the years passed, the rent and cost of utilities spiked. Tjahjadi found another loophole to keep the business somewhat afloat: she closed the seating areas to reduce the rent, leaving only the kitchen and a small storefront intact. It gave the place the feel of a pop-up. Tjahjadi developed a clientele that fell in love with her cooking, including Indonesian classic dishes such as Nasi Goreng (fried rice), Soto (a turmeric, chicken soup), and rendang (a spicy meat dish that CNN featured as one of the best dishes in the world in 2017).

This didn’t last very long. Java Village, the kitchen, became unprofitable and in 2017, Tjahjadi and her partners closed it down. To make up for the lost income, Tjahjadi became a nanny for a family in Manhattan’s Koreatown, while her business partner ran Indo Java. Opening and closing businesses is fairly typical among Indonesians as they scout for the most lucrative opportunities.

Every now and then, some of her old customers asked about her cooking. There was a demand for my food, so I thought why not, she said. With her only time off of being a nanny on Tuesdays and Thursdays, she began cooking a few meals in the small kitchen in Indo Java and sold them in 2017 (thus the name Warung Selasa, which translates to “Tuesday Food Stall”). She works out of her small three-by-four foot kitchen in the back of the shop and has attracted significant press over the past couple of years. She cooks only two days out of the week, charges a flat rate of $10 per dish, and has a fixed menu of one or two dishes for that day, which can be found on the day before on Warung Selasa’s Instagram account or through text messaging Tjahjadi.

A collection of dishes Tjahjadi sold in April and May 2020 (photos found on Warung Selasa’s Instagram account).

![]()

In none of Tjahjadi’s published interviews is there any mention of the US legal woes that beset the family for a decade. On a cold winter evening, Tjahjadi sat in a little bakery in Koreatown after her babysitting job and reeled out her immigration story.

When she arrived in 1999, she assumed that she and her husband were only in the United States so that they could earn some modal – financial capital – to build a business back home and rebuild their wealth. They lived in New York with the idea that this was temporary. Wanting to follow through with her plan, Tjahjadi dismissed the urging of her pastor at a church in Queens to report herself to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services and file for legal documents after her six-month tourist visa expired. Lawyers and other administrative costs would amount to more than $3,000 at that time and she reasoned that since they were planning to leave anyway, there was no real point in making such an outlay.

In the aftermath of 9-11, Tjahjadi’s immigration status hit a new and unanticipated obstacle: the Department of Homeland Security instituted the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS), which required all non-citizens of certain origins to register themselves. Coming from the biggest Muslim country in the world forced all Indonesians to report themselves to ICE. While this was happening, Tjahjadi found out she was expecting her first child. Unsure of what future her children would have back in Indonesia, they decided to stay in the United States.

First, they had to find an immigration lawyer. The USCIS website says there is zero cost to filing form I-589, a piece of paper that could save the life of a person. But a study by researchers at Syracuse University found that the chances of obtaining asylum are five times higher if the applicants are represented by an attorney. In 2017, judges denied some 90 percent of applicants without an attorney, while almost half of those with an attorney were successful in receiving asylum.

Tjahjadi asked other members of the congregation at church, many of whom have gone through the asylum-seeking process, about which lawyer she should contact. It seemed like everyone pointed her towards a Brooklyn-based immigration lawyer with a good reputation in the group. I thought I had a strong case – we were victims and my husband had stitches after the mob attacked, she said.

Under the Immigration and Nationality Act – the INA – the USCIS is required to schedule initial interviews within 45 days of an application filing with a decision to be rendered within 180 days. When these applications are “defensive,” that is, when a judge has denied these applications and the asylum-seeker wants to appeal, the applicants must go through a court system, which is notorious for its backlogs. The National Immigration Forum says as of 2018, there were over 733,000 pending immigration cases. The average wait time for these hearings was 721 days or about two years. Over the past decade, this backlog has worsened as funding for immigration judges has shrunk significantly.

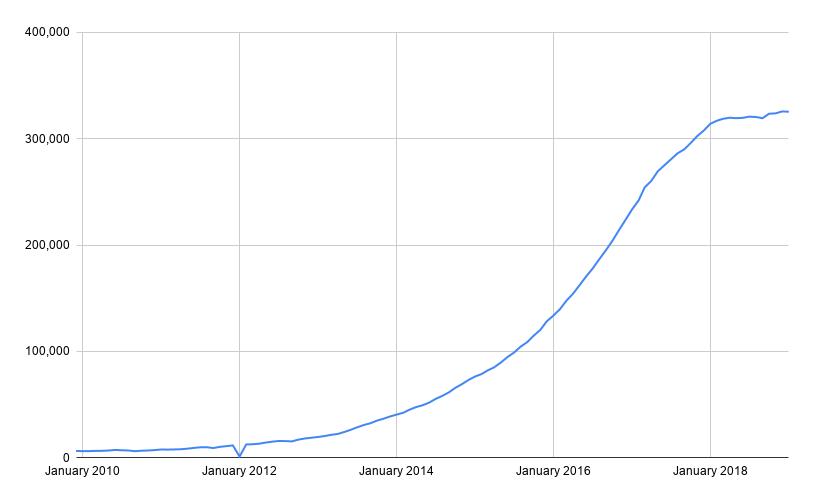

Pending affirmative asylum cases by month: December 2009 to January 2019

Graph 1: Pending affirmative asylum cases from December 2009 to January 2019 (Data obtained from USCIS and USA Facts)

Around 2002, the immigration office denied Tjahjadi’s initial application. The case was then brought to an immigration court in Queens, where her case was restarted twice—both a judge and an attorney had to be replaced—and she had to retell her immigration story a number of times.

The entire process, from asylum application to approval, to green card, took nearly 10 years. In 2012, Tjahjadi and her husband finally obtained green cards at a cost of more than $10,000 and countless hours, all while she and her husband worked at low-wage jobs. But she is one of the lucky ones. An estimated 115,399 immigrants filed for affirmative asylum applications in 2016 (with only 11,729 approved or about 10 percent), which is 39 percent more than the year before and a more than 100 percent increase since 2014. This is the seventh consecutive annual increase and the highest level since 1995, when applications reached close to 144,000. The number of pending applications for asylum climbed to almost 200,000 by the end of 2016, the highest number since 2004. And this is all before they, if needed, go to court to apply for defensive asylum.

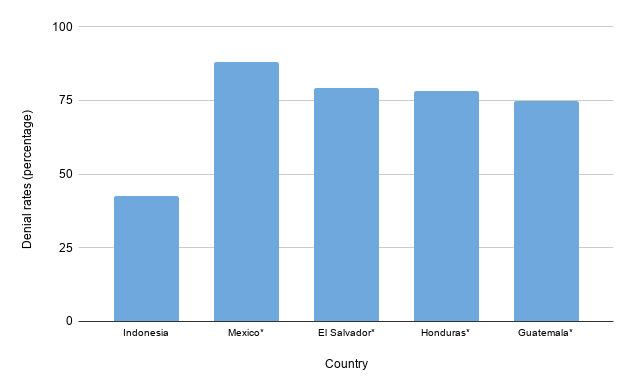

Chinese-Indonesians were lucky, in a sense, to have fewer legal obstacles than those of other immigrant groups. After 1998, active lobbying by Chinese American groups directed at politicians such as Rep. Carolyn B. Maloney of New York and Frank Pallone Jr. of New Jersey have contributed to an unusually high number of successful Chinese-Indonesian applicants for asylum. In the decade leading up to 2007, the US Department of Justice reported 7,359 applicants were granted asylee status and 5,848 were denied. Meanwhile, Latin American countries which have seen major increases in asylum applications have some of the highest denial rates between 2007 and 2012: Mexico (88 percent), El Salvador (79.2 percent), Honduras (78.1 percent) and Guatemala (74.7 percent).

Denial rate of asylum applications per country

Graph 2: Data for immigrants of these countries are between 2007 and 2012, while data for immigrants from Indonesia is from the decade before 2007. Additional data was not available.

The application process for asylum is daunting, and for many new immigrants, not many easily accessed resources are available to help them. In fact, there aren’t any resources telling them how to apply for asylum or how to become a citizen. Tjahjadi, for instance, wasn’t even aware she was in the United States illegally. She said, There were never any resources from the government – but I understand, if we were undocumented, how would they find us? All of the help she got was from her church community in Elmhurst. Her pastor advised her to get surat (the Indonesian term for legal documentation), to beware of ICE, and to get legal help for her four roommates when ICE detained them. The others in the church helped raise money when needed, and helped refer her to immigration lawyers when the time came. The cycle of help continued with one of her roommates, Wijaya.

Yet even after the couple obtained green cards for themselves and their two children, trouble still followed. In 2004, they were still sharing that three-bedroom apartment in Queens with four undocumented men – one of whom was Wijaya – whom they had met at the church. One day, a knock came at the door. It was five officers, with uniforms and all. They flashed me their badges and said they were with ICE.

I only let open a small crack in the door and they asked, “Does this man live here?” He held up a picture of someone who used to rent out a room in the basement of their apartment building, a man in his mid-twenties, who had come on a student visa, never ended up going to school, and had fled the apartment complex a few weeks before. He was undocumented and had said goodbye to Tjahjadi then, sensing that danger was near. I said to them, “No, I don’t.” I tried to close the door but one officer put his foot in the way. He asked, “Who else lives here?” I said, “My family.” He insisted on checking and Tjahjadi, feeling helpless, let them in. I had to wake my children and my roommates up. We were all scared. What they did not realize at the time, Tjahjadi said, was that ICE officers targeted them because these officers had tried to question their other Chinese neighbors about this man, but upon hearing the officers say “Indonesia,” the neighbors pointed them to her room. We were just unlucky, she said.

The men sat us down in our living room and one of them took out a tablet to check our names and our “surat.” When our roommates could only give them their tourist visas, which have expired, the officers confiscated their passports and told them to pick it up on Monday at the USCIS office in Manhattan. USCIS is considered the brother of ICE that deals with the administrative side of immigration.

As they panicked, her roommates considered ignoring the letter and running away from New York. But their church community advised against it. Our pastor told them, “The land you live on now is your home, the least you can do is follow their rules.” So the following Monday, Tjahjadi and her husband drove their four roommates to 26 Federal Plaza. The officers didn’t allow us inside the office, so we waited outside. After a few hours, an officer came to us and gave us their watches and keys. The officer told her to find a good lawyer. Unknowingly, she had delivered her friends to jail.

As grim as the reality might have been, Wijaya was strangely upbeat when he described that day. I took out all $700 that I had in my bank account because I was scared we would have to pay a lot for our passports. When they stepped into the office, all four men were told to leave all their belongings, except their wallets, in a bin. The officers were friendly and said we were on time, so we looked at each other and thought, “OK, this will be fast then because we’re following the rules so far.” But soon, without much being said to them, they were put on lock down and transported to a federal prison in Queens. After one month, they all appeared in front of a judge, who set their bail, so they could be released from detention, at $12,000 per person. (An immigration bond is to encourage attendance at a future court date and is paid to the government to secure the release of a detained immigrant. Only green card holders or US citizens can be the payee of this bond, and when the matter is resolved, the collateral will be returned. In 2017, the average bond was $8,000, but it is subjectively determined by the judge who takes variables such as detainee’s criminal history, risk of flight, and associations within the community into consideration).

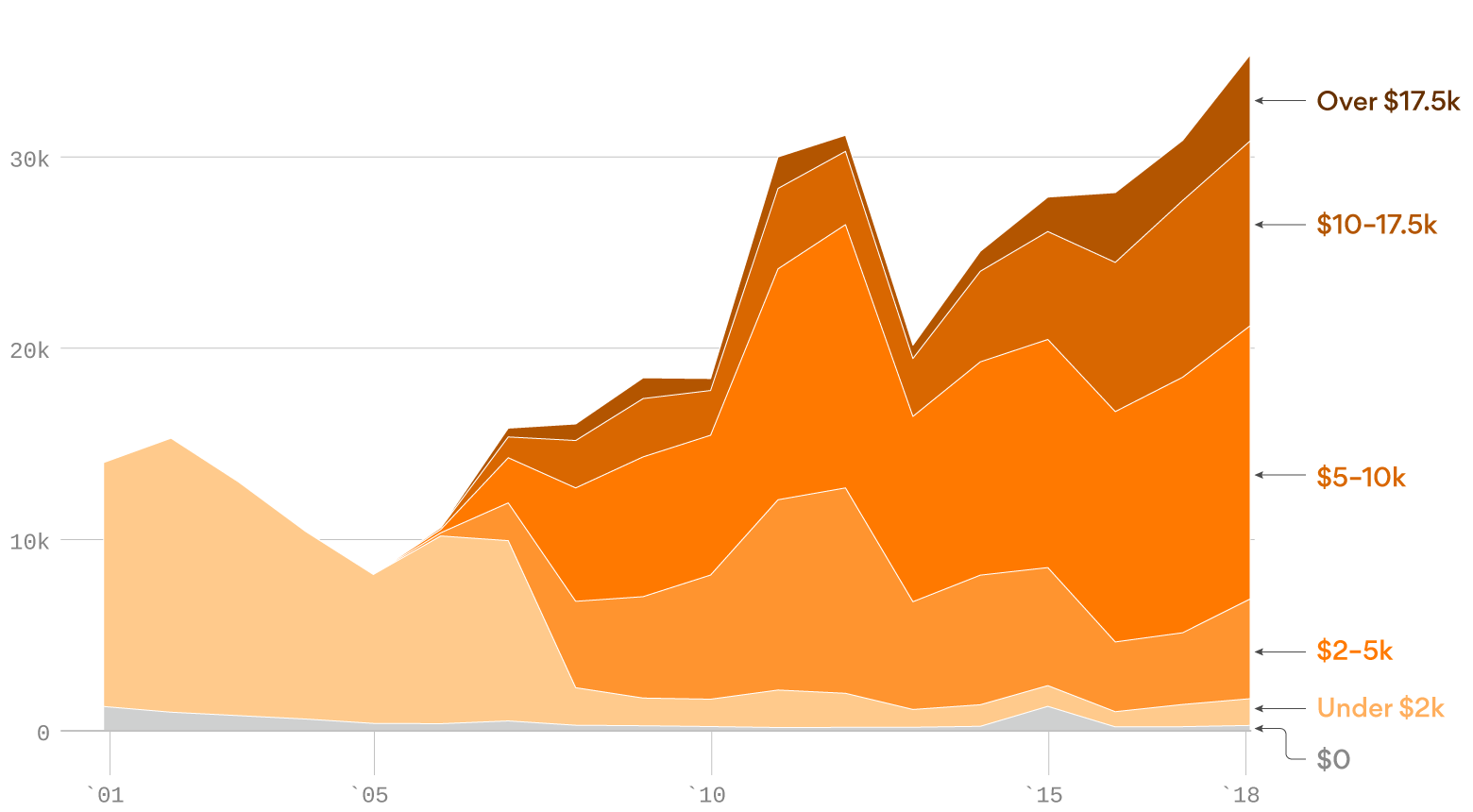

US Immigration Bail Bonds by Dollar Amount (2001-2018)

Graph 3: The dollar amount of US immigration bond bails from 2001 to 2018. In 2006, the median bond was $50, while in 2018, the median bond was $8,0000. Data and graph obtained from Axios and TRAC Immigration.

On the day Tjahjadi last saw her roommates, she immediately set out to find them a lawyer. She eventually met with lawyers from Christophe Law Group on Wall Street, who charged about $5,000 per case, plus a bonus if they won their cases. She managed to scrape together donations from church and other acquaintances, but not enough to cover the $12,000 for all four roommates, on top of the thousands of dollars of legal fees. She got desperate. I called all of their relatives, anyone they knew really to spare some money. I asked people at church, too, but they could only do so much. The legal bills piled up. Tjahjadi found it harder and harder to work, raise her children, and look out for her detained roommates at the same time. At one point, she even had to plead to the judges to get the court dates pushed back by a month because she ran out of money for the legal team. Eventually, a friend of hers who worked as a chef loaned her $5,000 and their legal battle continued.

Weeks later, on a Sunday afternoon after mass, Tjahjadi broke down to her friend at church. The judge said that for her roommates to be released, on top of the bail money, she also had to find a US citizen who had at least $50,000 in the bank to become the guarantor of each detainee. This meant that on top of finding bail money and paying legal fees, Tjahjadi also had to find four guarantors. After Tjahjadi’s friend comforted her, another acquaintance approached. We had a conversation about my roommates and all the fees, and it ended with him asking me to bring him to the lawyer’s office. I was a bit confused, but I did.

Meanwhile, Wijaya, who was 25 at the time, found jail quite calming. There were bunk beds, no cells, gym time, and different kinds of food everyday. It wasn’t bad at all. When the officers found he had $700 among his belongings, they made fun of him. They said, “Who brings money to jail?” But it was useful because then I could use it at the commissary to buy things like pajamas and a walkman. He said people were quite friendly with each other, and every other day they were allowed to watch a movie on the small TV.

Back in Manhattan, Tjahjadi’s acquaintance listened intently to the group of lawyers explaining how much she was to spend on getting her four friends out of jail. Her eyes began to water as she said, He told me he wanted to help, but he only had money to pay the $12,000 to bail one of them out, so I had to choose. I chose my closest friend who came from the same village as I did. It was not Wijaya. The whole board room went silent and asked him, “Are you sure?” Because that’s a lot of money to spend on someone you don’t know. But he was adamant.

As the meeting in that Wall Street boardroom concluded, and everyone was congratulating each other for being able to free at least one man, the acquaintance turned and asked if he could help in any other way. Someone mentioned becoming a guarantor. One lawyer asked, “For one person, sir?” and he said, “No, for all of them.” To release all four of Tjahjadi’s roommates, he would have to have $200,000, in cash or other assets. The court would never take this money away unless one of the guarantees does not pay the bond money. He thought about it for a second and then said, “Use my house as collateral. I already paid the mortgage off anyway.” We were all stunned.

This acquaintance of Tjahjadi was himself an immigrant from Indonesia, who came to New York in the 1980s and worked his way up a restaurant. As Tjahjadi told this story, she stared at her hands and started fidgeting. A tear rolled down her left cheek, followed by another. I got up to get her some napkins and told her to take a deep breath. It’s just, he’s a real guardian angel, and everyday I thank God for him.

While the guarantor issue was settled, Tjahjadi’s work was far from over. She still had to figure out how to pay the bail of the remaining three out of four roommates. She made dozens of phone calls to all their family and friends and managed to gather enough for everyone to get out, except for Wijaya. His story involved another miracle.

When ICE detained Wijaya in 2004, he was working as a food runner for a Japanese fusion restaurant in New Jersey. One of the men he was detained with was released early, and coincidentally, went on to work at the same Japanese restaurant Wijaya had. When the former detainee talked to the rest of the kitchen about him and Wijaya being detained in the same facility, Lauta, the head chef, said, If I give him the bail money, will you guarantee he pays it back? Once this friend made an agreement, the chef gave the $12,000 in bail money to Wijaya, a person he had previously only spent a couple weeks with. Later on, Wijaya was told about how ICE had detained Laota for immigration-related problems and was bailed out by a co-worker he barely knew. His total time in detention was two months.

![]()

Immigrants help their fellow immigrants in more than monetary ways. For Lily Kwan’s family, a Chinese-Indonesian who came to New York in November 1998, the immigrant community worked its magic similarly. A couple of years after her sister arrived in the United States with her two young children, they found themselves at a hospital. I don’t remember why or which hospital, Lily told me as we sat in a Panera Bread in Rego Park, Queens, but it was so important that she was there. As they sat in the waiting room, a friendly man struck up a conversation with her. He was from Greece, an immigrant too, and had just gotten his citizenship. My sister got along well with him, and at the time she was undocumented. The end result was this man marrying Lily’s sister and her obtaining a green card. They’re not together anymore now, but he gets along with our family so well, said Lily, I just saw him last week at a family gathering. He’s such a great man.

Wijaya experienced the warmth of the Indonesian community in another form: investments. In 2017, a group of fellow immigrants and himself pooled together $25,000 per person and bought a three-bedroom and two-bathroom house in Cleveland, Ohio. Now, they rent it out and split the $1,600 per month as a steady income.

After the Suharto regime had ended after May 1998, several presidents tried to reverse rules regarding Chinese identities. The Chinese-Indonesians were soon allowed to celebrate Chinese New Year (and the government recognized it as a national holiday), Chinese language schools were allowed to reopen, and Chinese names were welcomed once again, although many of the ethnic Chinese preferred to have both. But Amy Freedman, a political science professor at Pace University, said that these changes just scratch the surface of what is needed to protect the Chinese, and to an extent, other minorities. “What is needed is for someone from a respectable Muslim organization, and someone who is respected within the Muslim community, to come forward and not only show good relations with the minorities, but to also condone violent acts against them,” Freedman said. “Otherwise, there will always be tension.”

In recent years, there has been some evidence of further improvements, such as when Basuki Tjahaja “Ahok” Purnama, a Christian, Chinese-Indonesian politician, ran and won as deputy governor for Jakarta in 2012. But every once in a while, an incident will occur that seems to put the country back in the Suharto era. In 2017, a judge in Jakarta charged Ahok, who became governor to replace President Joko Widodo, with blasphemy after a comment of his regarding a government project was misinterpreted.

Indonesian Muslims protesting Ahok in Jakarta in Dec. 2016. (Photo by Getty Images for TIME)

Ahok, who at the time was running for governor again, was criticized for insulting the Quran and sentenced to two years in jail. He had mentioned that he planned to run for president someday, but soon after he was released in 2019, he recanted and said he no longer wants to be a public figure.

![]()

The way that the Indonesian government dealt with the aftermath of ‘98 has been abysmal. For a country whose motto is Bhinneka Tunggal Ika, meaning, Unity in Diversity, the protection it has for minorities is laughable. The population of Western Papua, for instance, is still involved in a conflict with the Indonesian government since 1962, caused primarily by the desire of the 3.5 million people of Western Papua to become a separate nation. Just last summer, the Indonesian police stormed through a dormitory in Surabaya and fired 20 tear gas canisters when a rumor broke out that the Indonesian flag was found in the gutter. 43 Western Papuan students were arrested and held in jail for nine hours before they were let go without charges. Nationalist vigilantes gathered outside this student dorm, chanting “Kick out Papua right now” and “Monkeys, get out.” None of the vigilantes faced any consequences, but several Papuan students found themselves injured at the hands of these rioters. The government and police did nothing. The event in Surabaya spawned a few other riots in cities throughout Papua.

Once most Chinese-Indonesian families have emigrated, they share an ideology of distancing themselves and their children from this part of their history. Wijaya and Tjahjadi, who both have two children now, have said that they do not see the benefit in disclosing the riots and discrimination they faced back in Indonesia. If they ask why we moved, I’d probably just say for better opportunities, Wijaya said. As Tjahjadi’s eldest daughter prepares for college in September, Tjahjadi said she does not think her children need to rehearse what she and her husband endured to get them where they are. They are American kids, Wijaya said, l’ll let them grow up that way.

When asked if they felt vengeful or sad in any way that the 1998 resulted in Chinese discrimination, most of my interviewees shook their heads. It was the norm, most said and for generations, they learned to live with it. Tjahjadi was no different. I just feel gemes at them, she said. “Gemes” is an Indonesian slang word that loosely translates to the state of going out of one’s mind in adoration of something, most likely something cute or adorable. One would not describe the events of May ‘98 as adorable or cute. But there is a softness to Tjahjadi using that word – she, like many, still have feelings of adoration for her home country.

![]()

Note: Most interviews were conducted in Indonesian and translated to English.