Chinese Students in the US

Worries in an age of uncertainty

by Emma Li

Tensions between the two countries are compounding the inviability of study abroad and overseas careers for Chinese international students.

Source: Getty

When Sichuan Airlines flight 3U8631 from Chengdu, China departed for Los Angeles on a Sunday evening in late August of last year, the plane was barely a third full but the passengers occupied more than half the seats, pushing back their armrests to sprawl comfortably across their rows while the cabin crew looked on in polite disapproval. For students more accustomed to 18-hour long plane rides filled with crying toddlers and dull in-flight entertainment, this felt like the ultimate luxury in long-distance economy class travel. It also signaled the switch of a decade-old pattern: For reasons ranging from antagonism abroad to new opportunities at home, the once-surging number of Chinese students who study at universities in the United States is in decline.

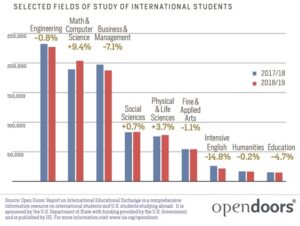

The differences are clearly reflected in annual data reports over the past half decade which show Chinese students enrolling elsewhere. For three consecutive years, starting in 2016, the numbers have been declining even though during the 2017-2018 academic year, over 33 percent of international students in the United States still came from China. That accounted for nearly a third of the money the international student population spent on tuition, fees, travel, and living expenses in their host country. The number of students enrolling for the first time at a US institution during the 2018-19 academic year fell by 0.9 percent, which was a recovery from the previous year’s sharp decline, but nonetheless a continued decrease. Most recently, in 2019, international student enrollment rates plummeted by more than 10 percent while enrollment in countries like Australia and Canada surged.

Interviews with Chinese students at US universities indicate an increasingly negative outlook on the overseas experience, contributing to a drop in new international student enrollment. These students are beginning to feel more confident about achieving social and professional success back home in China. The United States is combating theft of confidential research brought over to China by releasing statements of national security and putting stricter visa policies in place, but these actions are perpetuating suspicion toward innocent scholars. Chinese students are already facing issues on campus including xenophobic acts often fueled by political differences and more recently, the coronavirus. The consequence has been a declining trend of Chinese students studying abroad and instead, making the choice to go elsewhere or stay domestic.

The more recent appeal of homegrown alternatives includes higher chances for promotion within established companies and entrepreneurial opportunities. While Chinese students continue to make up a large percentage of student bodies throughout the United States and Europe, a strengthening sense of Chinese pride is making them more inclined to return home upon graduation. Their decision is directly impacting the business of study abroad facilitation agencies and revenue for US colleges. Talent particularly in the STEM and business fields is being outsourced as Chinese graduates turn to their native country for more fulfilling education and job prospects.

After living in Manhattan for nearly four years, New York University senior Yuhang Tang is still encountering day-to-day surprises when it comes to her identity. Tang recalled her decision to take a cab during an outing where she found herself in the company of a driver from Fujian, a province in southeastern China, who struck up a conversation. “You don’t look Chinese,” he said. “I think you’re more like an American student compared with other Chinese students I’ve seen here.” His comments astonished Tang, who was seated in the car with her roommate, another Chinese student. “You two look so outgoing, so lively,” he said.

Before Chinese students face the pressure of making post-graduation plans, they cite endemic campus issues—most prevalently, racial profiling—as reasons that deter them from wanting to stay in the United States. Many universities have been petri dishes of burgeoning xenophobia and are breeding grounds for anti-Chinese sentiment that has spread as fast as the fear of Covid-19. While people value the proactivity of hygienic practices during a time like this, this appreciation vanishes when they come in contact with Asians. Tang personally experienced this during the onset of the outbreak. “When we are wearing masks, we will be afraid of being identified or mistreated,” Tang said. “That’s something that I have in the back of my mind.” Wearing face masks is a cultural phenomenon that Asians and specifically the Chinese have been practicing long before the current pandemic. As social distancing and country-wide lockdowns have become the norm for Americans, they are also starting to change their minds about wearing masks.

As a Chinese international student, Tang finds herself oscillating between the practices of her native country and those of the United States. When she’s in China, Tang notes how her friends and family observe a more “international” air about her as she gets into more disagreements with her parents who are unaccustomed to her newfound tendency to initiate debates. Tang finds herself wrapped back into an international student identity once she returns to New York. The city seems to encapsulate her in a shell that classifies her in such a way that no matter how much she transforms, she cannot shed layers of the past.

Tang’s careful reflection has helped her realize that she doesn’t wish to stay in the United States for her entire career. Instead, she has plans to pursue grad school and eventually return to China. Tang’s decision has been influenced by recent events including FBI Director Christopher Wray’s statement on China’s position as a threat to national security. In 2008, China launched the Thousand Talents Plan to offer strong incentives for attracting foreign research contributions and talent. The Chinese Ministry of Education found that 339,700 Chinese students went abroad in 2011 and 186,200 graduates returned to China; 544,500 students went abroad in 2016 while 432,500 returned from overseas study. Wray warned that US universities should protect their foreign students from overseas coercion which has surfaced in the form of Chinese students reporting on research that they conduct domestically. “From the start as I arrived in the US, I have sensed this kind of negative impression towards the Chinese government, our party, and the students in general,” Tang said. As someone who finds her home between two countries that seem worlds apart in terms of distance as well as disparate ideologies, Tang is now required to make a difficult decision shared by other international students who are preparing to graduate.

“When the time comes to choose,” said Tang, “I’d have to think about all the contributions I’ve made and I would wish all the contributions would be made as a Chinese student to my country.”

Chinese students are worried that these public statements are instilling a hostile perspective by generalizing conspirators and innocent students within colleges. The Trump administration urged US universities to be more restrictive in the access they provided to students and researchers since a major reason for China’s continuously steady growth in science and technology is its booming export of students who study overseas. Cookie Qu, a senior at New York University, recognizes the danger in this line of thinking. “Nobody really knows what’s going on under the table. It’s not nice in the way that it’s spreading a stereotype,” Qu said. “You can think whatever you want and you can suspect anyone, but if you put it in the public media, it kind of gives an idea that Chinese people are all spies and Chinese companies are all spying on the US.”

Another student studying at NYU’s Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences, who asked to be identified as RL, is a STEM student who has been following the controversy. China’s Thousand Talents program also offers incentives for overseas scholars to return. Returnees can be guaranteed school placements for their children, and universities can also be rewarded for recruiting top talent. In many of these cases, the exchange is mutual. Domestic media is particularly attentive to the topic since the Communist Party of China organizes the project and attracts both US and Chinese-American researchers. “Their supervisors never told them that it’s not okay, and they just entered the project because the Communist Party is offering them very good offers,” RL said. “As researchers, they just can’t say no to that kind of opportunity.”

Nearly a decade after the program’s inception, it has continued to play a part in bringing students back to China. In 2017, the Chinese government reported that more than 80 percent of students who studied abroad returned, totaling a 10 percent increase within five years. Bloomberg reported that US-trained Chinese-born talent is becoming essential in driving the global expansion of Chinese companies and their hopes to dominate fields like artificial intelligence and machine learning. Wang Yi, a graduate from Princeton University, left his position at Google and returned to Shanghai where he launched a popular English teaching app that raised $100 million in 2017. Kevin Diao was 29 years old when he also followed a path to success by securing a Wall Street investment banking job that earned him millions of Chinese yuan a year after graduating from NYU. He decided to return to Beijing and established Meixin Finance, a wealth management company that has raised tens of millions of dollars worth in investment.

A 2019 congressional report revealed the US government’s efforts to deter China from stealing intellectual and commercial property in academic and industrial settings, notably by issuing visa restrictions. RL has noticed an impact on STEM students in higher education. “The Trump administration openly expresses their doubts and skepticism many times about foreign academics and calls us thieves,” she said. “It directly affects what my degree could possibly provide me. Now there’s a [lower] chance of me working in the US.” These changes inevitably affected researchers as well, which in turn has led to losses in innovations and advancement for the United States. Weihong Tan, previously a chemistry professor at the University of Florida, fled to China during an investigation of alleged fundings he received from his native country. Now, Tan has been conducting vital research since March in an effort to develop a quick and efficient test for the coronavirus in China.

Other victims have also been caught in the two countries’ crossfire. In August 2019, Air China announced the cancellation of its regular Beijing-to-Honolulu flights due to a decrease in demand for service. China’s internal changes, including the country’s expanding job market and the airline industry’s selectivity, are manifested abroad through students who spend extensive periods between China and the United States. These Chinese students carry new perspectives that crucially inform both countries, an impact that’s bound to diminish as fewer Chinese students fly back and forth to study in the United States.

![]()

The inability to travel in air also made this past Lunar New Year on Jan. 25, while many universities were still on winter break, especially taxing. The expected demands of the festivities are innumerable hours of cooking in the kitchen. This year, like the number of hours to be, the sudden onset of a respiratory illness later identified as the novel coronavirus introduced even more stressful burdens that disrupted the holiday atmosphere. Before long, Chinese students who were preparing to return to school in the United States found themselves facing even more challenges.

Source: Getty

A few days after the Lunar New Year, the Department of State issued an advisory that banned travel to China. An equally if not more vicious pattern of discrimination started to emerge when individuals in the United States tested positive for the coronavirus. Xenophobia seemed to be spreading more potently than the virus itself as students began to witness anti-Chinese sentiment on college campuses. The University of California at Berkeley’s University Health Services posted an infographic on Instagram that listed xenophobia as a common reaction to the outbreak. During the first week of February, NYU sent out two emails outlining guidelines for responding to the coronavirus, specifically addressing NYU students and staff who had recently traveled to China. “I remember when NYU sent out the first email on the coronavirus and how they’re going to detain students,” Tang said. “The dean in my major—she’s from China—wrote on behalf of her position saying ‘This email is really inappropriate. I perceive it will cause a negative influence on Chinese students. I think NYU should be more supportive and welcoming to students.’ I think there’s been a change and another email was released later on.”

Misdirected fear toward Chinese students leads to unnoticed consequences that only exacerbate their existing identity conflicts. College campuses throughout the country have reported cases of xenophobia-driven acts of hate. Prejudice toward foreigners is spreading fear that’s fueling the further marginalization of the same group. On campuses like NYU where international students and correspondingly, Chinese students, make up a large proportion of the overall population, the prejudice is often directed toward this cohort.

This fear is also experienced across the country at the University of California system where Chinese students make up the largest subset of the international student body. Meredith Xu, a senior at University of California, Santa Barbara, has often observed the social habits of her cohort. In most of her classes, Chinese international students sit in groups and complete projects together, contributing to a strong sense of community. Despite this usual feeling of belonging, Xu became increasingly aware of her international identity around the end of January. A rumor started to circulate around campus about a student who had returned from Wuhan, China after winter break and was showing symptoms of a fever. “I felt pretty self-conscious even though I didn’t travel to China for a while,” Xu said. “I was afraid thinking what if I had a cold and I kept coughing, and people would think I have coronavirus.”

More recently, Trump’s messages continue to muddy the waters and exacerbate anti-Asian sentiment. Eric Hu, a senior studying political science and economics as Skidmore College, has been attuned to the effects of these statements. “If you violate the political correctness, for example, like Trump using the phrase ‘Wuhan virus’ or ‘Chinese virus,’ nobody can really do anything to him,” he said. “It’s a big problem. If equality is really the major spirit of the US, Americans need to do something to define that.” This shifting of blame is becoming the main strategy for Republicans who are persistent in holding China accountable for spreading the virus. As a political science major, Hu is especially disappointed by how the Trump administration has dealt with the crisis. “I think the US politicians always do one thing: when they have internal pressure, they tend to [transfer] it to foreign countries,” he said. “You can blame China if you want, I respect your thought, but it doesn’t help with the rapid increase in cases. You have to do some real stuff to solve the problem instead of blaming others.”

On a surface level, it appears that new masses of students from China continue to be attracted to the prospects of studying in the United States on both the graduate and undergraduate level. US News & World Report ranked NYU as the seventh university with the most international students in 2020, making up 20 percent of its student body. Mitchell Stephens has been a professor of journalism at NYU for nearly 44 years and has witnessed many changes firsthand. The New York City campus was mostly Caucasian a few decades ago, and gained its status as an international center after making significant efforts to enroll more people of color. The appeal of a new country known for its immersive style of education is a strong motivator for international students seeking a study abroad experience. “I do think there is this openness to questioning that is not present in all parts of the world,” Stephens said. “There’s a tradition of student expression and questioning and challenging that Chinese students encounter a little bit more in American-style classrooms like NYU Shanghai and if they come over to NYU in New York, that many of them find challenging and invigorating.”

When classes began during the past fall semester at NYU Shanghai, faculty members quietly agreed to remain silent about the Hong Kong protests which were headlining on a domestic and international level. Similarly, the university’s Hong Kong student association told the New York Post that remaining politically neutral was in their best interest. “I am aware that students who grew up in China and particularly have family in China are not growing up in a situation that has political freedom that we enjoy in the United States,” Stephens said. While this difference hasn’t directly affected Stephens when he teaches Chinese students in New York, he was cognizant of it when preparing to teach a journalism course at NYU Shanghai.

Students in support of Hong Kong protesting before NYU’s Human Rights in Hong Kong panel. (Source: Ishaan Parmar for Washington Square News)

On Nov. 18, 2019, the NYU School of Law welcomed a panel of human rights activists and scholars who reflected on the unfolding crisis in Hong Kong. RL arrived at Lipton Hall near Washington Square Park on the Monday evening of the panel, interested in attending the fully reserved event. She found herself standing before two camps of students representing either side of the protests, along with reporters from local media and Chinese news outlets. The panel proceeded with divisive responses from audience members, many if not all of which RL gathered to be pro-mainland. “I don’t know how many people went there in order to learn more about the issue,” she said. “I do think that inviting all three panelists from the Hong Kong side is a very clear message, or at least NYU acknowledges it.”

As the talk went on, all the nuances of the conflict surfaced. A student from Yunan, China whose mother is from mainland China and father is from a region in Hong Kong made memorable comments that RL recalled. “She was basically saying how ever since this whole situation broke out, whenever [she] talks to her mainland friends, the first thing they ask is, ‘Oh, why do you support violence?’ and she said that makes her very hurt,” RL said. “Her voice began to tremble and she began to cry, and it was a very emotional moment. I think both sides cooled down a lot after her speech.” Chinese students at NYU and other colleges in the United States feel hesitant about participating in subjective discussions on civil liberties. They feel pressured to embody both countries’ ideals, and media coverage exacerbates their burden as it shows the consequences for those who express support for one side.

This response is dissonant with the pride NYU takes in its culturally and ethnically diverse student body. During September, college students fly into Manhattan from all corners of the world ranging from Antigua and Barbuda of the West Indies to Asia’s North Korea, Myanmar, and Yemen. They take part in a wave of human migration that involves over 17,550 individuals planting their roots in the heart of Washington Square Park which blossoms with diversity by the start of the academic year. With the steady incline of foreign student enrollment, NYU established the International Student Center, or ISC, two years ago. Since then, the Center has served as a hub of opportunities for international and domestic students to interact on a global scale.

![]()

During the first few days of September, Welcome Week is the university’s most concerted effort to absorb and integrate all of its newcomers. The ISC hosted regional hangouts including events for East Asian students to engage with one another. Unfortunately, the process didn’t turn out to be so straightforward as the ISC staff found themselves laboring over the puzzle of how to label the sessions for Chinese, Hong Kong, and Taiwanese students given the political tensions between the countries. While grouping the former two regions together as well as separating them would both lead to a stalemate causing disapproval among Chinese and Hong Kong students, the ISC was relieved when their Taiwanese event didn’t ignite any backlash. The effects of international politics were already starting to take root within NYU.

Endemic issues have also infiltrated the campus, exacerbating the pressures that Chinese international students face. These students are exposed to an array of new demands that they’re often unequipped to face, from cultural disconnects like unfamiliar cuisines to a lack of explicit resources for addressing their concerns, and sometimes, though less often than in the past, deficits in English comprehension. Allen McFarlane, the Assistant Vice President for Outreach and Engagement at NYU, believes that more can be done to build on the university’s existing efforts. This includes the International Student Transition Program, where international students apply to arrive at NYU a week early during which they are assisted in getting connected to the school. Another cornerstone of their efforts is the Residential International Student Engagement, which helps international students in residence halls make connections within their communities while supporting their transitions. Freshmen are paired with roommates who are different from them. “It might be regional, or international,” McFarlane said. “We’re thinking of creating diversity within the first few months of their time here at NYU.”

These initiatives are meant to address the lack of mutual communication between certain cohorts of international and domestic students, which has created a cycle of misunderstanding that disrupts the rhythm and nurturing environment necessary for international students to fully integrate into their community. As a Chinese student who’s deeply involved with her cultural club on campus, Cookie Qu calls for a two-way exchange between local and international students which she believes can begin at the fundamental level of mutual understanding. “What they’re not doing is encouraging the local students to interact with international students,” Qu said. “We have culture clubs at NYU that host different kinds of events. A lot of clubs are trying to introduce their cultures to students, but those events are voluntary so only the people who are originally interested would go.”

Jamie Remmers, the assistant director at NYU’s Center for Student Life, said that change can start within the classroom. Throughout the academic year, Remmers organizes events such as Global Buddies at the International Student Center to promote greater engagement across student cohorts. Every semester, the program pairs international students with domestic students who are asked to facilitate their peers’ transitions into American culture. After a month of advertising, the ISC saw 15 pairs of students participating. “Out of those 30 students, six are domestic. But the idea we initially wanted was one domestic one international student,” Remmers said. “We have to have this reflective conversation of [asking] ‘Why aren’t the domestic students coming?’”

Despite the marketing and advertising that’s been put in place, Remmers hopes that a better balance can be achieved with the help of other university departments. “There’s only so much that we can do here because we’re three levels away from their engagement. A student has their academics, the next is maybe a club, and we’re out here,” Remmers said. “I think a lot of it has to start with the academic departments making workshops mandatory. When I was a grad student in Steinhardt, it was mandatory for us to do diversity workshops.” Remmers also considers the Residential Life and Housing Services at NYU as the ideal starting point for social justice initiatives. While workshops are helpful, behavioral changes take time to develop. Her considerations reflect those of McFarlane, who believes it will be worthwhile to focus on freshmen roommates. “So what happens when a first year student is paired up with an international student? Who is staying together the second year?” he asked. “We’re trying to look at points of integration and then points of separation and see if we can play off of those.”

Just as domestic students have their role to play in this exchange of understanding, international students must recognize the need to come to terms with differences between their native and American cultures. “It’s really frustrating to see that students from mostly East Asian countries feel these microaggressions,” Remmers said. “That’s something that’s talked about so much within administration. We can say it, but it needs to be from the students that people start paying attention.”

This introduces a paradox for Chinese students who are unused to a culture that encourages individuals to be outspoken. There are fewer instances that demonstrate this better than the American classroom where participation often counts towards a portion of students’ final grades. RL feels pressured to voice her opinions, regardless of how much they directly contribute to the discussion. This is a stark contrast with what’s expected of her back home where she was taught to listen to the teacher.

“Before you talk, it’s more important for you to think through, sort of like playing the role of a mirror in the classroom,” she said. “I always think of myself as a facilitator. In the US, I feel like I’m kind of actually a character or a protagonist even.”

Her first exposure to this new way of thinking occurred at the end of high school when she was applying to colleges in the United States. “I was very used to the Chinese style of doing things, which means that there is someone to tell you what you’re supposed to do next,” RL said. But the application process required her to venture into new territory by using VPN as well as Google for the first time. Without a counterpart to the advisers available in US high schools, many Chinese students turn to zhongjie, third party companies that provide the same services and much more for a profit.

In 2017, the Chinese government no longer required study abroad facilitation agencies to get licenses from education bureaus, making it harder to ensure that they don’t commit fraud. The Chronicle of Higher Education reported in 2013 that Zinch China, a consulting company that advises American colleges recruiting Chinese students, estimated that 90 percent of applicants submit false recommendations, 70 percent have others write their personal essays, and 50 percent have forged high school transcripts. While most of these students simply seek editors to proofread their work, low-performing students often don’t write anything. “I’m very critical about the industry,” Liu said. “It’s part of the reason why there are so many incompetent students here. They don’t do the work themselves.”

But as more students worry about their prospects of studying in the United States, the agencies have become more popular than ever. The Beijing Overseas Study Service Association and its extension, the China Overseas Study Service Alliance, are membership-based organizations made up of 300 study abroad agencies, agents, and institutions in Beijing and greater China. Between 2017 and 2018, some 30 percent of all outbound Chinese students employed a member agency registered by one of these two organizations. Paris Liu is a student from Beijing now pursuing her second graduate degree from NYU. “When I was applying to NYU, my parents found an education institute in Beijing and they really wanted me to use it,” Liu said. “I think for them, it’s more of a comfort thing because if you use the service, it’s not going to harm you. It’ll either benefit you or do you nothing.”

JJL Overseas Education Consulting & Service Co., Ltd is one of the first study abroad service providers to be jointly approved by multiple Chinese government entities. Company data indicates that nearly 57 percent of Chinese students studying abroad do so with the help of an education agent. JJL Overseas, for one, uses social media marketing to recruit student clients. Favored software for this purpose are QQ, for instant messaging, and Sina Weibo, for microblogging. On Sina Weibo, Chinese students tend to be particularly receptive to content from the West. Another major player is the multi-purpose social media app WeChat which has over 980 million active users and is growing increasingly popular as a communications vehicle for agencies and prospective students. Liu also gained experience working with study abroad agencies in China during the four years between her two NYU experiences. “I definitely saw students worried all the time,” she said of those she worked with in China. “One student was asking on a QQ group chat if anybody knew anything about the current application situation, whether it’s still easy to get a visa. You can see this sort of anxiety.”

Chinese international students are far from a single homogenized group. The cohort is made up of individuals from provinces and cities all across China. The sheer size of the population often makes the college experience less united for its members. There are social and economic differences as well. The application services do present a financial burden for many families with service packages reaching as high as $8,000 to $10,000. Top students who are even more concerned about securing a spot in prestigious schools are regular customers. While many Chinese students are privileged enough to hire a study abroad agent and others hail from high schools within the United States, RL’s less traditional educational trajectory required resilience during the application process. Over the years, she has noticed that fewer students who share her background are enrolling at NYU. As she talks to Chinese freshmen and sophomores in her classes, RL finds that all of them have been in the United States for a long time or attended high schools in the United States at the very least.

The future is changing even for a student like RL for whom a US education was a more elusive prospect. “I never really wanted to move to the US. I see the US as a window for me to enrich myself, but everyone has very different agendas,” she said. “In my case, I do want to do a PhD program in the US but I’m going to work for a year first.”

Eric Hu is also planning for his return back home. When Hu first arrived in the United States, he had deep admiration for the country and its economy, technology, and education. “When I actually stayed here for four years, my views have changed a lot,” Hu said. “I thought the US was the place I wanted to live for the rest of my life but now I just want to finish my education and go back to China.” In recent years, many students from RL and Hu’s generation have already been actively doing so.

![]()

During the fall, in the freshwater Yangcheng Lake a couple miles northeast of Suzhou in China’s Jiangsu province, farmers harvest medium-sized burrowing crustaceans known as mitten crabs. They migrate towards the Yangtze delta into the traps of local fishermen who sell them to the markets of cities like Shanghai and Hong Kong. Some are merely “bathing crabs,” dunked in the lake for a few hours then sold with genuine lake-raised crabs that attract higher market prices. Haigui, or sea turtles, are even more highly prized delicacies.

The two creatures have become symbols of Chinese students who study abroad and return home to work. A bathing crab is tentative and uncertain of a future career path once back home. Meanwhile, haigui, prized by Chinese companies, have figured out how to capitalize on their experiences overseas. But both may be imperiled species if current trends continue. The impact of policy change surrounding admissions and visa requirements has become a major factor in the decision-making process. Recently, the United States restricted F-1 visas for international graduate students studying STEM fields to one year while they had been allowed five years in the past. These policies have especially impacted fields including high growth sectors like robotics and technology. “In the past, it was a hierarchy thing,” Liu said. “The top students go to America, the students who are in the middle will try to pursue a masters degree in China, and the worst students would go find a job.” But with the cost of higher education increasing in China, the expense of studying abroad has become about the same or even less than enrolling in college at home.

All of this has led to a new wave of discouragement for the once popular choice of studying abroad. China’s Ministry of Education has warned students about the risks of shorter visas being granted, and Chinese parents are increasingly unwilling to send their children abroad in light of the unpredictable policies. Even international graduates face challenges on their return home. Despite the global perspectives, language skills, and prestigious education that are supposed to help them secure work, they are disadvantaged without a professional network and even experience difficulty reintegrating into their own culture. “Chinese parents are sometimes worried about the situation. For one thing, it’s not anything crystal because we don’t know what’s going to happen,” Liu said. “It’s just this sort of uncertainty which worries people most of all.”

The rise of homegrown alternatives, including the growing Chinese economy, are also factors tempting Chinese students to return home after graduation. Large tech companies like Tencent and Alibaba grew by about 10 percent between 2015 and 2016, and are worth more than a trillion dollars combined. “Living in China for the past four to five years, I’ve experienced the convenience of life and the prosperity of the country since I’m from Beijing,” Liu said. “I can understand why this sense of patriotism is getting stronger… China is really developing rapidly and people are feeling that life in China is better.”

C9 League’s Tsinghua University located in Beijing. (Source: Shutterstock)

Chinese universities are also climbing up world rankings as the government increases investment behind its C9 League universities, which is China’s equivalent of the Ivy League. The city of Hefei in Anhui province is home to the University of Science and Technology of China, a member of the C9 League. Along with its national prestige, USTC is an attractive option for Chinese students who crave open access to Google and other sites that are blocked around the country. Although the university’s acronym is not to be mistaken for “United States Training Center,” Liu said this has often been the case for prospective students who are seeking an edge in gaining admission to US higher education institutes.

In 2013 the National Science Foundation reported that 92 percent of Chinese graduates with US-minted PhDs remained in the United States after finishing their programs. The Chinese government introduced a new policy in 2017 that helped foreign students find work after graduating. Initially, students were required to obtain work experience before receiving job offers in China, which made it nearly impossible for them to secure a job upon graduation. The new policy allows for foreign students with postgraduate degrees or higher to be offered employment within a year after graduation.

While bathing crabs are falling out of demand in China’s marketplace, haigui have retained their desirable status just as turtles have long been known to be symbols of wisdom, wealth, and longevity in Chinese culture. Rather than being seen as symbolic objects of delicacy, haigui have reaffirmed themselves into equally coveted positions as overseas returnees and the future of China.

![]()

Time and again, recent events in this uneasy political climate have demonstrated that the future of Chinese international students is not so easily determined. Guoxi Zhu, a senior studying physics at Brandeis University, has a lifetime of experiences that stand as a testament to this. Zhu first visited the United States in 2010 with his father, a professor in China who was invited to Georgia Institute of Technology as a visiting scholar. After spending a year attending middle school in Atlanta, Zhu returned to China with his father, but kept the possibility of returning to the United States entertained in his mind. When he arrived in Boston a few years ago as a newly enrolled student at Brandeis, Zhu was disappointed that the college didn’t meet his expectations in providing a cosmopolitan experience. Just as Chinese students are now considering study abroad opportunities outside the United States, Zhu turned elsewhere, specifically Europe, to continue his education.

Around that time, tensions between the United States and China were escalating. In comparison, the relationship between the United Kingdom and China wasn’t as volatile. Zhu arrived at Oxford University for his one-year study abroad program as one of many “freshers” from China, most of whom had applied to schools in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Zhu attributes this to the ongoing US-China trade war which came with a lot of uncertainty at the time. Before long, the amount of Chinese students studying in the United Kingdom started skyrocketing.

Following the rise of the Hong Kong protests, Zhu started to publicly express his support for the protestors. Before long, Zhu’s high school friends realized that his Facebook page was pro-Hong Kong. “They got very angry and they even cursed me for being a supporter,” Zhu said. “That was the moment I realized how much I appreciated the conversations I had with other Chinese students even if we didn’t agree with each other’s points of view.”

More recently in February, Zhu found himself in the face of another crisis. The coronavirus travel restrictions were interfering with his return from a reporting trip in Ethiopia. During his flight back to New York City, Zhu was held up at Customs and significantly delayed from boarding his flight. Due to the policies at the time, his Chinese passport was being searched for evidence that he hadn’t visited China in the past few weeks. Eventually, Zhu was cleared and allowed as the last passenger to board the plane.

Now that Zhu is a senior, he’s reflecting on his past as he makes steps toward building his future. “Before coming to college, I actually wanted to study aerospace engineering. But I gave up that thought because there were and have been some restrictions on that subject,” he said. “At some point, I felt lucky that I didn’t end up pursuing that because the restrictions got worse in recent years especially for Chinese students.”

At this point, Zhu is feeling uncertain about US immigration policies, finding a job, and staying in the United States after graduation when his visa expires. He’s not alone on this, as many of his friends have changed their majors in order to extend their visas. Zhu’s cousin graduated from NYU and went on to pursue a successful STEM career at companies like Microsoft and Apple but was employed for years without a stable working visa. After a decade, she finally received her green card.

As another STEM student at the mercy of her identity as a Chinese international student, RL has concerns for her future well ahead of landing a prestigious job. With expectations to pursue a higher degree but restrictions that prevent her from doing so, RL anticipates that her chances of getting accepted into leading PhD programs is at risk. With all things considered, returning to China seems to be her best option. “In China, I feel as if I am one of many and I can just walk on the street without thinking that I am a foreigner,” RL said. “I’m not thinking that I need to represent anything. I’m just myself, whereas in the US, people definitely see you as a symbol of something. I don’t know what that thing is, but it feels like I am not myself. I am more than myself.”

![]()