Disparities of Displacement

How the livelihoods of Gazan and Syrian Refugees in Jordan Compare

by Celina Khorma

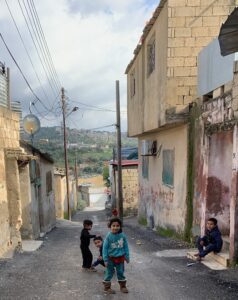

Photo by Celina Khorma. Children at the Gaza Camp in Jerash, Jordan

“Do you hear that?” Mahmoud tapped the ceiling, a thin sheet of metal. It had begun raining and hailing almost two minutes earlier and every drop, which fell faster and with more force as the storm progressed, hit the roof with the sound of an alarm clock you couldn’t turn off. “That’s the music of the Gaza Camp.” It was a tune no one danced to, but he smiled anyway. Mahmoud, who lived in the camp his whole life, was used to it, appreciative even – for at least the roof was made of zinc and not asbestos.

Gaza Camp, known formally as Jerash Camp, is only a 40-minute drive away from Amman, Jordan. It’s the worst off of all refugee camps in the Kingdom, where refugees outnumber its nationals in several municipalities. Some camps are organized by the crises that sparked their plights: 13 for Palestinians, five for Syrians, and more where refugees from an additional 56 countries reside, including Yemenis, Sudanese, and Iraqis. But not all camps are created equal, nor are the circumstances for the people they house. Zaatari camp, the primary Syrian refugee camp in Jordan, and second biggest refugee camp in the world, suffers only a fraction of the safety, infrastructural, and economic issues that are widespread at the Gaza Camp. And even though refugees from Gaza and their descendants have been in Jordan since 1967, it’s the Syrian refugees who receive the better opportunities in the Kingdom today.

Palestinians brought waves of immigration to Jordan during the 1948 Nakba and the 1967 Six-Day War, and those from the West Bank, which the Kingdom annexed in 1950, received full Jordanian citizenship. They were even able to retain it after Jordan cut ties with the West Bank, as Oxford University’s Philip Robins has described, so long as they resided in the East Bank of the Kingdom at that time. Those living in the West Bank received green cards, granting them travel access between Jordan and the West Bank. UNRWA, the UN agency that oversees the Palestinian crisis, says that today, the majority of Palestinians in Jordan still hold citizenship, but these figures don’t include the 158,000 Palestinians who fled from the Gaza Strip. Political and legal loopholes have rendered the Gazans stateless, and their descendants suffer the consequences, too.

Gazans in Jordan are often described as “doubly displaced,” having fled to the Gaza Strip during the 1948 Nakba, then to Jordan during the Six-Day War. Because Egypt occupied the strip at that time, these Gazans held Egyptian travel documents, and having entered the Kingdom under Egyptian authority, were deemed ineligible for Jordanian citizenship. They, in turn, live almost rightless among the other Palestinians in Jordan, who are now considered equal to native Jordanians before the law.

The Gaza Camp bears the marks of that unfortunate legacy. Wastewater runs through its rocky pathways, asbestos roofs held down with cinderblocks are common, and 52.7 percent of the camp’s residents, both the original refugees and their descendants, live below the poverty line. Even those who live outside of the camp in broader Jordanian society are struggling. Without citizenship, Gazans have limited or no access to education, real estate, or the workforce and find it nearly impossible to earn a living.

The issues are made even starker with recent budget cuts for UNRWA. The Jordan Times reported that at a Nov. 25 meeting of UNRWA’s advisory committee at the Dead Sea, Christian Saunders, UNRWA’s Commissioner General, said the agency is in the midst of “worst financial crisis” ever. Without the immediate infusion of $167 million, needed in order to provide the bare minimum of agency services, the newspaper reported him saying, “we cannot survive.”

Oroub El-Abed is a postdoctoral fellow at SOAS University of London who researches the Palestinian diaspora in Jordan. In an interview, she explained that Jordan accepted the Gazan refugees in 1967, and even built the Gaza Camp to host them, assuming their stay would be temporary. But when Egypt barred their return at the end of 1968, El-Abed said Jordan had no choice but to absorb them.

The Government of Jordan gave these Gazans travel documents similar to those Egypt had issued, known as two-year temporary passports. The documents do not include a raqam watani, a national ID number, therefore making the right to work, study, own property, and vote in the kingdom almost nonexistent. On top of that, the documents are costly to renew.

Jordan’s nationality law, El-Abed explained, specified that those who lived in the country between 1946 and 1954 were eligible to obtain Jordanian citizenship. Gazans technically did not meet the criterion. “Yet there is another article within the nationality law,” El-Abed said, “that says if an Arab person lives in Jordan for more than 15 years –– the key word is an Arab foreigner, not any foreigner –– this Arab person would have the right to apply to the Jordanian citizenship.”

Gazans technically fall under this category. “Jordan excluded the Gaza refugees from this particular article,” El-Abed explained. “The claim is that this is a way to make sure that Jordan is not naturalizing Palestinians and Jordan will continue to claim the right of return for these people. It’s a way to safeguard the nationality.” Some, mainly the higher class, have been able to acquire full citizenship through political and social connections, yet only 6% of the Gaza Camp holds Jordanian citizenship today, and without a national number, rights are scant.

“I think the most important thing is to give them access to the rights of the citizen without the citizenship.”

Michael Vicente Perez is an affiliate professor at the University of Memphis and the University of Washington. He wrote his dissertation on Gazan statelessness in Jordan, and spent two years in the Kingdom conducting research. “There’s almost a sense in which being Gazan is a sense of not belonging to Jordan,” he said in an interview. “I think the most important thing is to give them access to the rights of the citizen without the citizenship.”

Unlike the Gazans, it was a civil war, not occupation, that sparked the plight of Syrian refugees and sent them streaming into Jordan starting in 2011. Extending citizenship to them was never considered, and it didn’t need to be. With the help of UNHCR, the European Union, and various other countries and international organizations, Jordan was able to provide Syrian refugees, both in and out of camps, with sufficient help to get them back on track. Eventually striking a billion-dollar deal with the EU, known as the Jordan Compact, the Kingdom was even able to provide Syrian refugees with work permits, free of charge. Almost 200,000 have work permits today, according to UN reports.

UNHCR, the UN agency that oversees the Syrian crisis in Jordan and elsewhere, grew out of the 1951 Convention on Refugees, which was ratified just a few years after the Palestine-Israel conflict began. By then, UNRWA was already up and running, which meant that all Palestinians, including Gazans, fell outside the Convention’s umbrella, as well as the aid UNHCR administered. Since then, the agency has grown significantly, and receives far more international funding and recognition than UNRWA does. Jordan is not a signatory to the Convention on Refugees, meaning the regulations are not officially enforced. Still, the Kingdom’s legislation pretty much mirrors those set forth in the Convention. According to the UNHCR, “a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) establishes the parameters for cooperation between UNHCR and the Government of Jordan on the issue of refugees and asylum-seekers.”

The inequalities between UNHCR and UNRWA services are evident, too. Zaatari officials are strict when it comes to granting outsiders access into the camps, especially if the outsiders don’t plan on doing volunteer work. I, myself, was unable to enter Zaatari, and instead relied on reports and personal testimony from a woman who used to live there. Conversely, entering the Gaza Camp was simple. In fact, it was so simple, I didn’t even need to obtain security clearance. After driving for 40 minutes from Amman to Jerash, plus an additional 10 minutes scouring through sideroads, I found myself at the camp. No checkpoint, no security –– just a slow drive along the uneven streets that with each passing minute began to look more and more rundown.

![]()

A mother of three who used to live at Zaatari, and who wishes to remain unnamed, sat down with me to describe life in the camp. We met in Amman over sweet mint tea and mixed nuts, and I thanked her for going out of her way to chat. Some of her family members still live in Zaatari, so she makes the trip there frequently. “The day I came, the camp still only had tents,” she said. “Communal bathrooms. Communal kitchens. If you wanted to cook, the kitchen had working gas for everyone. You went and waited your turn, and most of the time, all stoves were occupied.” It was tough, but positivity sustained her during the transition. “I thought, would you rather sleep on the rocks and sand, or go back to Syria?”

The camp, which has become the fourth largest ‘city’ in Jordan, bustles with Syrian pride, as its residents attempt to make it feel as homey as possible. “Of course, it’s still a camp,” she said. “You can’t go in expecting it to be like how Syria was. But when you accept your situation, you really appreciate it.” Despite the camp’s problems, like unstable heating, the woman added that most of the people she knows at Zaatari would rather stay there than leave. Basic essentials, like electricity, are covered for them, leaving the money they earn from work to be spent on other necessities.

All three of her children have completed university, and one was even able to continue studying medicine in Canada. None of this would have been possible without the UNHCR. “The UNHCR is beautiful,” she said. Education, at both secondary and university levels, is a main priority. A fact sheet released in June 2019, states that “18,338 children [in Zaatari were] enrolled in 32 schools, with 58 community centres offering activities.” And boys and girls were relatively equal among the schoolchildren, too: 49% of them were girls, while 51% were boys. In 1992, the UNHCR also launched a scholarship program for refugees who wish to pursue higher education, known as DAFI (Albert Einstein German Academic Refugee Initiative). Syrian refugees in Jordan continue to reap the benefits of it today.

A total of 106 students at Zaatari alone received DAFI scholarships in 2019, according to a UN fact sheet released in January, 2020. But Zaatari isn’t the only refugee camp in the country to house Syrians. Azraq Camp and Emirati Jordanian Camp also have primarily Syrian demographics, and even refugees who don’t live in camps can receive DAFI scholarships, making the number of total recipients for Syrians even higher.

The internal infrastructures of Zaatari’s communities and residential areas have also seen lots of improvement since the camp’s inception –– one such improvement includes a plan known as the Zaatari Wastewater Network. Completed in 2017, the plan has ensured that all homes in the camp are connected to a proper sewer system, and that each household is equipped with “the simultaneous construction of private toilet facilities.”

UNICEF also launched a sustainable water and sanitation network at Zaatari in March 2019. The system provides refugees with access to 35 liters of water a day, all from the faucets in their caravans –– a significant improvement from the communal water tanks residents formerly relied on. The network has reportedly reduced operating costs by two thirds, according to UNICEF, and was also partly funded by Germany, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States.

Homes in Zaatari are modest –– at both Zaatari and the Gaza Camp, shelters were built to be temporary –– but their infrastructures account for far less health hazards than Gaza Camp does. In Zaatari’s early stages, refugees either lived in tents, made of canvas, or caravans, which are sturdier and help protect against harsh winter conditions, according to a report conducted by MIT. As of 2016, caravans have replaced almost all tents, now accounting for 99% of all homes at Zaatari, according to an article in the Journal of Architecture.

UNHCR, surrounding countries, NGOs, and the Kingdom of Jordan all fund housing at Zaatari. Saudi Arabia reportedly spent $75 million constructing 24,000 caravans for the camp. Original plans intended for these to be laid out in a grid structure for access and safety purposes, but local communities have instead reorganized the caravans in a “U-shape”. Camp residents found that this was one way for their new camp neighborhoods to mimic the structure of communities back home in Syria. It also provided a common meeting ground between homes. “Neighbors come by for coffee. There are seating areas outside, and we’d invite people over,” the woman said. “They live the Syrian life.”

Syrians pride themselves on craftsmanship. The woman’s sister, who still lives at Zaatari, has four caravans. In them, she’s developed space for a living room, another area for guests, and even a garden outside. For the refugees, making Zaatari feel as close to home as possible was key in easing the transition. Another man who had also built a garden outside his caravan, which he decorated with a fountain, picnic table, and olive trees for his children, explained, “one enjoys spending his time with these things, to forget what happened to us and forget the grief.”

The trade of caravans has become one of the main sources of income at Zaatari. Reorganizing the caravans to the refugees’ desired layout created a new market demand: movers, and the necessary moving supplies. As a result, Syrians in the camp worked to acquire items like “fence posts from the camp walls to use as large axles and [attach] wheels to them,” to build cart-like vehicles for pushing and moving caravans around Zaatari, according to an Oxford University report. These movers have been dubbed “removal men.”

But the refugees have done more than rearrange caravans to spruce up their homes and communities. In collaboration with international aid agencies, they’ve even repurposed materials to make furniture items like “shop shelving, signage, and general household items,” according to the Oxford report. These are primarily constructed from the wood floors of old caravans.

Caravans have dually become spaces of residence and work opportunity, with many refugees selling and trading caravans to create small shops. These exchanges are technically not approved by donors, but a 2014 study found that approximately 64% of Zaatari’s businesses operate from their caravans. To the refugees, trading these unneeded caravans for business purposes made more sense than returning them to the UNHCR.

But the yearning for the Syrian quality of life still lingered like a mirage on Zaatari’s horizon for those refugees attempting to make the camp feel as close to home as possible. Basic services are provided, but getting the little luxuries refugees craved—be it sweets, home antiques, or clothing—was up to the refugees themselves. Small businesses, which also included catering and tailoring services, emerged discreetly, but soon became one of Zaatari’s main sources of income. Since then, the market has only expanded. Today, the camp bustles with a thriving marketplace and economy of its own: a refugee-run souk that grosses around 10 million JD a month, around $14.1 million, according to the UNHCR.

The street in the camp, which is now lined with almost 30,000 stores and restaurants ran out of caravans, has become better known as Zaatari’s very own Champs Elysées—or, more suitably, the Shams Elysées. Quite obviously, the name is a play on the well known Parisian boulevard that houses some of the world’s most luxurious brands, but it’s also a nod to their home-country, Syria, which in Arabic, is called Al-Sham. Some of its stores include a bridal store for women to purchase wedding gowns, and even a pizza delivery service brought to caravan doorsteps via bike-riding couriers.

Officials have debated the legality of refugees working inside the camp, but they’ve concluded that even though the refugees do not pay taxes to the Jordanian government for their sold goods, it’s still a way to keep money circulating in the camp; the work is often described as “illegal but tolerated.” It also helps refugees build entrepreneurial skills.

Business extends beyond Zaatari, too. Thanks to a $2 billion plan known as the Jordan Compact, refugees can also work outside of the camps. According to an Overseas Development Institute fact sheet, the compact, signed at the London Conference in 2016, “combines humanitarian and development funding through multi-year grants and concessional loans” to ensure that Jordan issues 200,000 work permits to Syrian refugees. The permits are only valid for certain sectors, the report adds. Prior to the inauguration of the compact, refugees were required to pay for work permits at the same rate as other foreign residents.

The compact tackled education as well, and intended some of its funding to go towards enrolling all Syrian refugee children in schools. While school enrollment still isn’t as high as anticipated, UNICEF has stated that in 2016-17, some 126,127 Syrian refugee children attended public schools, as well as private and certified camp schools.

The International Labour Organization and UNHCR have even established an employment office at Zaatari and Azraq, another large Syrian refugee camp in Jordan. It’s not only a space refugees use to find jobs, but it also provides other services, such as counseling and training.

Of course, UNHCR is not the only agency that offers aid to Syrian and other refugees. Ruwwad, with locations in Jordan, Egypt, Lebanon and Palestine, describes itself on its website as a “non-profit community development organization that works with disenfranchised communities through education, youth volunteerism and grassroots organizing.” Founder Fadi Ghandour developed a program for marginalized youth that has become the crux of the organization: The Mousab Khorma Scholarship Fund, or MKYEF. In exchange for community service at Ruwwad, the MKYEF provides youth in Jordan who suffer socioeconomically with scholarships to university. Ruwwad works with both Syrians and Gazans, as well as other marginalized groups in the Kingdom.

Alaa is one of the scholarship recipients. He and his family, up until 2011, called the small Syrian town of Homs home, a place he can no longer imagine through any other lens but war. He was in university studying math when the war struck Homs. “We went to another city and it got attacked,” he said. “Then a week later, we moved to Damascus.”

pull quote flush left “My biggest dream is to help refugees all over the world, not just in the Arab world.”

But it didn’t take long for violence to spread even to the capital, which quickly became unsafe too as more refugees from throughout the country fled there. It was then that Alaa’s father decided to relocate the family to Jordan, where a close friend of his lived. Alaa stayed behind to study at the University of Damascus. But six months later, as the war escalated—“At one point, there was a shelling attack on the University of Damascus itself”—he joined his family in Jordan. “My mom just couldn’t . . . . She said I either had to join them, or they would come back to stay with me.”

Alaa made the move in early 2013. “The hardest moment of my life, first, was leaving our home in Syria,” he said. “And the second was the five months I spent in my room in Jordan, not knowing anybody.”

His dreams for the future are fairly simple: to keep studying in Jordan, maybe get a Masters degree abroad, and even work for the UNHCR. “My biggest dream is to help refugees all over the world, not just in the Arab world,” he said. Halfway through our conversation, he paused. “Maybe after twenty, thirty, forty years, I can start thinking about going back to Syria and just see it,” he added. “Because when we remember Syria, we remember war, refugees, not a nation we carried. I remember planes dropping bombs and rockets. The tanks. The people.”

![]()

Around an hour’s-drive away from Zaatari at the Gaza camp, there hangs a cloud of anguish that silences the laughs of children playing in the streets. Poverty rates are the high: at 52.7%, the most impoverished in all of Jordan. And the effects are rampant. The camp takes up around 0.75 square kilometers of space, but houses some 30,000 refugees; by contrast, Vatican City is around 0.44 square kilometers with a population of 1,000 people. Overcrowding and hazardous living conditions are commonplace, and freely flowing wastewater has, until recently, remained one of the most dominant issues at the camp. A project conducted by the SDP in 2017 has established proper sewage systems for most homes. But for many, the issue still remains unaddressed.

A New Humanitarian report said that “sewage and waste water [was] either released through holes in the floors of refugees’ homes into a concrete maze, or dumped straight into ditches running under their homes.” The EDA added that the runoff even flowed through children’s playgrounds, increasing the risk of “diseases related to the contamination of drinking water and direct contact with wastewater,” particularly for the children. Precarious walkways and a foul stench have afflicted the camp as a result.

In 2017, the SDC and DPA completed the first phase of their project: the building of an underground sewerage system for homes in the camp. The goal was to reduce illness, particularly diarrhea, for adults and children, and fortunately enough, the system also provided new job opportunities for camp residents. The issue has become far less widespread, and the maintenance of the network has since been handed over to Jordanian authorities.

One mother of three’s response to how she manages to make light out of the camp’s ubiquitous hardships was only, “We’re living, it’s normal.” This is life as she, and everyone else, knows it. The woman has seen the camp improve over the years, especially in her area: the roads have gotten better, they’re paved now, and for that, she’s thankful. Her main priority is her home.

Photo by Celina Khorma

Three people live in this room, which is actually a step above many other homes at the camp. According to FaFo, “17% of all households comprise nine or more members, which is more than twice the average for” other Palestinian refugee camps. Along with Hussein, Tabliyeh and Wihdat camps, the Gaza Camp is among the four “camps with the lowest median per capita square metres of living space.” On top of the crowding, the walls of the woman’s home are so fragile that parts of it, if scratched, crumble down to form a pile of rubble on the floors: the dusty pile of rocks that her home was built on. Her roof was also improperly installed, leaving an opening for rain and dust to enter her home.

Still, the success of the SDP plan hasn’t been shared by all camp residents. An UNRWA teacher, Mahmoud, who resides in the camp said that roads are still not paved in the more impoverished areas of the camp. Those areas lack a proper sewer system, too, making not only the walkways unsafe, but even more pressingly, the drinking water. This is one of the ditches in the camp, where wastewater occasionally still flows through.

Photo by Celina Khorma

Tap water in most regions of Jordan is unfit for consumption, but even more so at the Gaza Camp. A mother of seven, who is pregnant with her eighth child, still doesn’t have access to safe drinking water at her home, but her children drink from the faucet anyway. There isn’t any other option. She said that their bodies have evolved to tolerate the water, and that nearly everyone at the camp will take whatever they can. Her eight-year-old son, standing in the middle in the photo below, has been diagnosed with cancer.

Photo by Celina Khorma

Photo by Celina Khorma

Mahmoud gave me a tour of the camp when I visited in January. Natalia Papadopoulou, who has been raising money and donations to conduct repairs in the camp since 2015, joined as well. Just after taking me to the ditch, an older woman who lived a few feet away tapped Mahmoud on the shoulder. She knew both him and Natalia, essentially the camp’s superheroes whose powers include repairing asbestos roofs and raising money for necessities like food, heating, surgery, or even trivials like a TV. The woman asked if they could visit her home, only a few feet away, to examine a leaking problem.

Jerash gets a fair amount of rain during winter, which complicates camp life even further. Unstable roofs are widespread: some are made of zinc held down with cinderblock and others are made of asbestos, which, if improperly installed and inhaled, is a health hazard. The roof in the woman’s home, however, was made of neither substance. It wasn’t made of any metal or solid at all, but instead, a thick sheet of fabric.

Photo by Celina Khorma

Unsurprisingly, water leaks through everytime it rains, and the makeshift roof offers no insulation. As a result, the cold and moisture-related perils make her home nearly uninhabitable. And for others, infrastructure is only one of the reasons why life at home is so difficult. One mother of four who asked Ms. Papadopoulou for monetary assistance has two disabled children. She described them as mu’akeen, the Arabic equivalent slur for “retarded,” then slung the orange shawl over her arm. Behind her, one boy sat, hugging his knees, rocking back and forth while crying atop a thin mattress. Another, slightly older, faced Ms. Papadopoulou, smiling at the sight of a new face. “My husband married another woman because I kept giving him retarded children. Our other two kids are normal.”

One of her sons is 23 years-old, and the other is 18. But both have the bodies and build of preadolescent boys, a result of the hereditary blood disorder known as Thalassemia. The condition requires frequent blood transfusions, a burden complicated further yet by the Gaza Camp’s lack of facilities. “Thank God,” the woman frequently said with a smile, tenaciously bearing the mindset that, still, things could be worse.

Clouds hovered above Jerash then, signaling the rain and hail that was soon set to fall. The woman’s home is much like every other at the Gaza Camp –– exposed, frail, and capped with a metal roof held down with cinder blocks. “We don’t have anything. The gas finished two days ago. I’ve been cooking on this,” she said, pointing to the charcoal burning in a metal tin on the ground. The call to prayer was sounding.

According to UNRWA, Gaza camp contains the highest concentration of Palestinian refugees who aren’t covered by health insurance, at a staggering 88%. Unlike UNHCR, UNRWA does not provide healthcare to refugees. Instead, the agency “offers free or heavily subsidized preventive healthcare and limited curative medical treatment to its beneficiaries at its health centres,” according to the same FaFo report. The Civil Insurance Program (CIP) and the Royal Medical Services (RMS) are two of the most common forms of health insurance for Palestinians. FaFo adds that CIP “covers all government employees and their dependents, poor people, the disabled, Jordanian and ex-Gazan children below six years of age,” while RMS “covers military and security personnel and their dependents.” Other types of insurance include those provided by universities and work, as well as private insurance.

CIP and RMS insurance are governmental services that national number-holders are entitled to. Considering most Gaza camp residents are stateless, it’s no surprise that only 12% of the camp holds any form of insurance. And with some of the highest poverty rates in the Kingdom, the idea of getting private health insurance for those at the Gaza camp feels like something out of a fantasy.

UNRWA reports that approximately 75% of the camp’s homes are unsafe for habitation. According to a Palestinian Return Centre report, over “65% of roofs are still made of rusted asbestos sheets and corrugated zinc,” both of which are breeding grounds for disease, especially cancer. El-Abed described Gazan life in Jordan as a seemingly endless limbo. However, she said, “Survival mechanisms do exist at all levels.”

At one of the camp’s preschools-slash-womens’ centers, light rain began to trickle atop the zinc roofs during my visit on one January afternoon. “We don’t have heating. It’s hard to save for soba heaters and gas,” the woman who runs the center said. Her eyes were heavy, and she looked tired. But her vivacity somehow shone through anyway, coloring the otherwise small, dull room we sat in. “It’s all based on the center’s budget, and we don’t have the budget to spend on that.” What she primarily intends for the markaz, Arabic for center, is for it to be a space where women in the camp can actually request and receive help.

Most of the issues these women face stem from poor economic situations, and statelessness only makes entering the workforce thrice as challenging. The center finds ways to help. The woman and the board decided to combine the women’s center with a preschool, so mothers could access training while keeping their kids at school just a few doors down: all for a 6 JD tuition, approximately $8.46. It’s expensive, but far more affordable than others, she said.

“I love the kids. I die for them,” she added. “We cook for them, donate things – a lot of jackets in winter. Let me show you some pictures.” After stumbling across a selfie of hers – “That’s me, don’t I look good?” she said with a nudge – the woman proceeded to show me images of the kids in classrooms, who were smiling with their donated items. Next, she swiped to a photo of a workshop session for the women.

pull quote flush right “Look at the beach we have,” she said.

“We do all kinds of workshops for women: self support, socializing, confidence building, enabling, strengthening.” With a sense of urgency she added, “Women in the camp need these things. They have many stresses on them: family stress, economic stress. And the worst is the economic stress because that’s what causes the family stress.” The rain began to fall heavily, and almost ironically, one of the next photos she showed was of a leak in the center. “Look at the beach we have,” she said.

While the preschool has enhanced camp life significantly, secondary and elementary school-enrollment at the Gaza Camp is still low. According to a FAFO report, approximately 14% of camp residents above the age of 25 have never received any level of education, and only 10% have received a secondary-school education. Even at noon, children take to the camp streets to play outside, rather than convene in a classroom.

El-Abed explained that in the early 2000s, as Jordan began taking on the strain of other refugee crises along its borders, regulation changes made Gazans even more vulnerable. She said that Jordan permitted the new Iraqi refugees to access public schools so long as the UNHCR paid their fees. Essentially, the rule served as an effort to regulate these refugees, and states that only those able to pay the 60 JDs annually—about $85—can attend public schools. “Jordan, until really, really recently, was giving Gazans the rights to access public school,” she said. “They suddenly had a 60 JD-fee imposed on them. And because they are not like the Iraqis, there is no UN body that covers their education. Iraqis were able to secure the support from the international community.”

UNRWA provides free-of-charge schools for Palestinians in Jordan. They’re mostly inside the camps, which discourages many out-of-camp residents from attending because of transportation costs, according to an UNRWA and Fafo study. The proportion of students in UNRWA schools who haven’t completed basic schooling is also higher than those at public schools, the study added: “29 versus seven per cent inside camps and 23 versus ten per cent outside camps.” Enrollment rates are staggeringly low, partly because access to university is even harder to attain than secondary schooling. That in turn discourages Gazans from attending any school at all.

Palestinians and their descendants also don’t qualify for DAFI, like Syrian refugees do. Instead, the Government of Jordan distributes 300 scholarships to public universities across the 13 Palestinian refugee camps, Perez explained. This means that larger camps have better odds than smaller ones, and as such, Gazans typically claim only 26 of those seats per year. Another option they have would be to apply to Jordan’s universities as foreigners—a highly competitive process.In that instance, El-Abed said, Gazans would need to apply through the Palestinian embassy to benefit from the tiny 5% quota that is reserved for the foreigners coming from the Arab countries. Tuition fees would also be higher.

At the Gaza camp, there is no employment office. There’s no international, billion-dollar compact that seeks their incorporation into the workforce either. Even for those with university degrees, finding employment remains daunting. When Syrians fled to the Kingdom, a new law was passed that raised the price of work permits for foreigners from 170-370 JD ($240-$522) to 500 JD ($705), which, depending on the job, is sometimes higher than that. Because Gazans and their descendants are not considered refugees, this fee applied to them as well. El-Abed said that eventually, a committee in the Jordanian Parliament, called The Committee of Palestine, waived the fee for Gazans, too.

“At one point myself, I really thought that the problem was the money,” El-Abed said. “To our surprise, when we went down to the field, we discovered there was another problem.” New regulations also put limits on who can work in the public sector and therefore made it extremely difficult for Gazans to gain such employment. That has led many to turn to the high-risk informal sector. While conducting research, El-Abed spoke to a 50-year-old Gazan man who was stripped of his previous position as a school director. “The man is highly professional. He’s well educated,” she said. But when the law came into force, the school he ran requested his resignation. “The schools cannot really protect him,” she said, “because there is now a regulation that is imposing on the public sector: who to recruit, in what positions and in what kind of jobs.”

Some Palestinian refugee camps, like Wihdat and Baq’aa, have their own souks that neighbors and non-neighbors alike frequent, but Gaza Camp has no bustling marketplace of its own. Perez described the camp as more “geographically marginal” than the others, and even ten minutes from Jerash, its precarious conditions give those who don’t live nearby even less of a reason to visit. “That means that the economic conditions of the camp are less robust than some of the other places based on their position, and that means there is less money in the camp,” he said. “Less money means there’s less opportunity for building and repairing things.”

As a result, life is bleak. Desperate for an empty lot to run around and play in, children take it upon themselves to claim spaces of their own: one being, officially, a cemetery. Teenagers and kids gather for picnics, play sports, and socialize amid the graves. The camp has only one playground, leaving its youth with few other options. If not at the cemetery, they perhaps take to the rocky streets to kick a soccer ball around until it’s time to head home.

Photo by Celina Khorma

Still, Perez pointed to the positive, declining to reduce Gazan life to its suffering. “You also see weddings in the camp, you see people hanging out and socializing. It’s a dynamic place,” he said. “I saw both things, hardship and ordinariness.” Children play on Xboxes and Playstations, and there is even a beauty school in the Gaza Camp. Among its toxic conditions, there are still attempts to make life the way it used to be, to make it, somehow, feel normal again. But it almost feels like there’s no light at the end of the tunnel. Gazans don’t have a glass ceiling to break. For them, it’s an asbestos covered roof.