NYC Special Ed Failing

A review of NYC’s special education in public schools shows a broken system with little recourse for struggling families.

by Sarah Jackson

At the pediatrician’s office with her then-18 month old son in 2007, Amber Decker received the first inkling that her son might be different. Her pediatrician had asked how many words her son knew. Five or six, she said. Much to her shock, his vocabulary was supposed to be 10 times larger. “I was horrified, and I didn’t understand,” Decker said. “I was like ‘Really? He’s so young.’ So I started looking at other kids and realizing that there was something going on.”

Decker put her son in Early Intervention, a New York City program that provides services for children three years and younger who are “behind in developing skills compared to other children their age.” The evaluation confirmed the fears her son’s pediatrician had stoked. Her son was performing below the third percentile in language and fine motor skills. Through the program, he received speech therapy for the next year and a half.

At three years old, when all students in Early Intervention age out of the program, he was bounced to the Committee on Preschool Special Education, the city’s special education arm for children ages three to five. His new evaluation determined he had Pervasive Developmental Disorder – Not Otherwise Specified (PDD-NOS), a catchall diagnosis for autistic people whose condition does not fully meet the criteria for a specific disorder on the spectrum. “He’s very bright but can be difficult,” Decker laughed.

With a name, albeit murky, for his condition, and his continued speech services, the boy went to NYL William O’Connor Midwood School in Brooklyn, a special education preschool, until he turned five.

This is where the trouble would start for Decker. With nearly a quarter of a million students classified as having a disability, New York City’s special education system is the largest in the country, swallowing up even the size of Houston’s entire public school student population. But its gargantuan size has meant not that it is too big to fail, but that it has become prone to failure, operating out of compliance with a federal law on special education for the past 13 years, according to the 2019 New York City Department of Education Compliance Assurance Plan.

In interviews with parents from every city borough, a patchwork of issues became apparent. Schools unable to render legally required services, often as a result of slashed funding. Teachers missing signs of special needs in a student until it is too late. Parents lacking the knowledge and support structure to navigate the complicated special education process. And now, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, students falling behind with online learning, unraveling the threads of the painstakingly earned progress they had made before. With a broken system, and often narrow, complicated paths to any recourse, the burden of improving the system often falls on the shoulders of parents, community advocates, and even lawyers in some extreme cases.

PULL QUOTE RIGHT: {{{{{ “It was horrendous; the kids had no services,” Crissie Bertone said. “Everything was a big facade.” }}}}}

In Decker’s case, as her son transitioned into elementary school, she hoped he would be admitted into the ASD Nest Program, an inclusive education model for higher-functioning children with autism. A key component of the program is the now-prevalent Integrated Co-Teaching classroom, in which students with disabilities learn alongside their neurotypical peers with the instruction of two teachers, one for each specialization. At a meeting with Department of Education employees, she brought up the possibility of including the integrated classroom in her son’s Individualized Education Program, or IEP for short. This is a legally binding document that lays out an educational plan tailored to each student with a disability. Here, parents and the city’s Department of Education lay out specific services the child is entitled to receive, such as speech therapy, a paraprofessional to assist the student throughout the school day or even placement in a smaller classroom size to receive more individualized attention. Both parents and the DOE must agree on the parameters drawn in an IEP in order for it to go into effect. The document, which must be reviewed annually, also covers the child’s strengths and weaknesses and sets goals for the year.

Decker’s request was denied in the IEP meeting, where parents and the DOE review the child’s medical evaluations and make their cases on what services the child should receive. The DOE suggested she seek out private schools after refusing her son placement in ASD Nest. When private school placement didn’t work, Decker enrolled him in an Integrated Co-Teaching class outside of ASD Nest for two years. There, she says, he was the only student in his class with autism. With every haphazard placement, the DOE seemed to be saying, “You guys all have IEPs, we’ll throw you all into a big class and cross our fingers and hope it all goes well,” Decker said.

The boy who had flourished in kindergarten now exhibited behavioral issues, leaving during the school day and falling behind in his academics. In second grade, the DOE removed his speech services without conducting an evaluation to prove he no longer needed them. He started to regress. He started using pronouns incorrectly. He began to memorize and repeat words from other situations in regular conversation, an autistic behavior known as scripting.

In one incident that Decker says inspired the work she now does as a special education peer advocate, her son’s Queens public school called 911 to take the boy to an emergency room because he had refused to take off his Spider Man Lizard mask. In third grade, his teacher, desperate to get him to do work, bribed him with tennis balls in a bizarre calculus that offered nothing more than short-term solutions and a strained promise to make up for the failures of an entire teacher training system with a backpack full of tennis balls.

When he managed to scrape by to fourth grade, Decker dug up her previous efforts to secure her son a placement in ASD Nest. With the help of a lawyer, she prepared to file for an administrative hearing through the Impartial Hearing Office, a last resort for parents who believe their children with special needs haven’t received an appropriate education. There, an attorney conducts due process hearings to adjudicate disputes between parents and the DOE, weighing both sides to determine what, if anything, went wrong and deciding how to rectify the situation.

Her plan: to sue the DOE into placing her son in the highly esteemed program. Where DOE employees wouldn’t help get her son into ASD Nest before, the faceless data troves and records on the DOE’s website could. Decker got her hands on previous impartial hearing decisions, published with redacted names on the website, and used them as a road map for her own son’s case.

But the territory was still uncharted; she had never gone through the Impartial Hearing Office. “The parent has to be the driver — and it’s a lot of driving,” she said. But she couldn’t yet see the roads. With both hands on the wheel, she enlisted a Queens attorney to subpoena five IEPs of kids already in the ASD Nest program. Decker compared them to her son’s IEP to make sure it really would be the best program for a child with his specific conditions. Emboldened by her research and the extent to which her son fit the ASD Nest profile, she and her attorney finally filed for an administrative hearing for placement in the program and won. “I shouldn’t have to be an advocate,” she said. But “at the end of the day, no one’s going to fight like a parent will for their kid and for what their kid needs.”

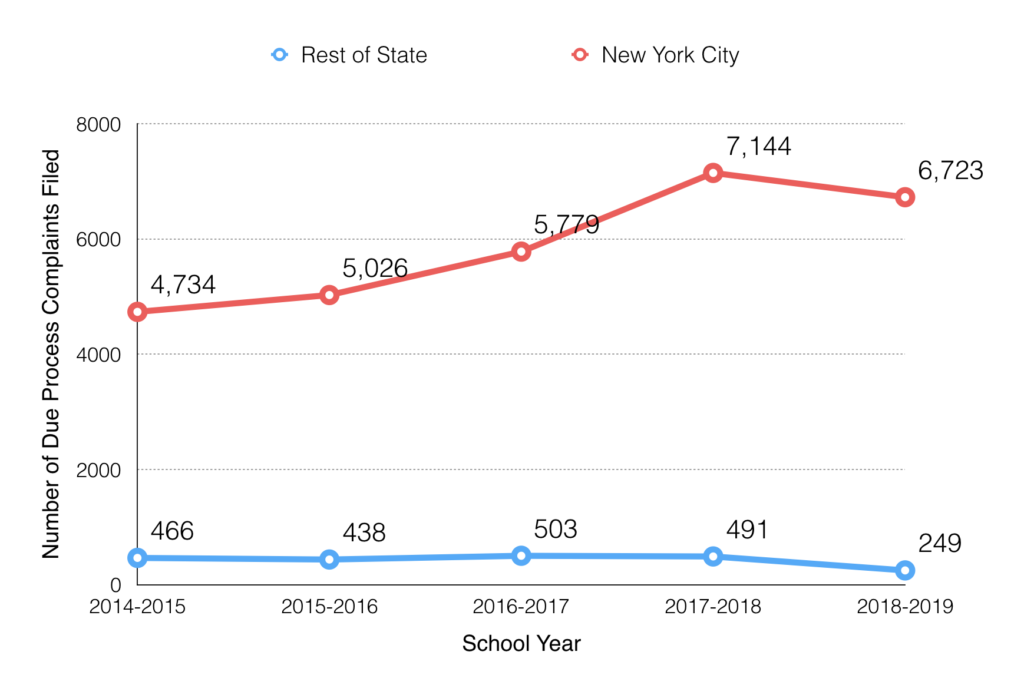

Decker is one of a sizable handful of parents who only found recourse after strong-arming the DOE into a legal case. New York state holds the unsavory record of receiving more special education complaints about due process than any other state in the nation. In the 2018-2019 school year, a whopping 96 percent of those complaints were traced back to New York City’s beleaguered educational system, popping up like toy moles that the DOE, riddled with bureaucratic failures, must keep quashing to keep going. That year, the city’s Impartial Hearing Office, which processes disputes between parents and the DOE, received over 6,700 due process complaints from parents. For parents entangled in this arbitration, contentious IEP meetings and inadequate services rendered are just temporary fixes, like tennis balls filling in for real special education teaching strategies, until they can sue for what their child really needs.

Once complaints are filed, it’s anybody’s guess how long resolution will take. In New York state, the length of time that a case remains open “far exceeds” the timeline set forth in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, a federal law ensuring free and appropriate public education for students with special needs, according to the 2019 DOE Compliance Assurance Plan. In the 2018-2019 school year, the average length of a case in New York City was 225 days. That’s 125 percent longer than the state’s required minimum length for an entire school year.

Graph created using data from the 2019 External Review of the New York City Impartial Hearing Office. The number of due process complaints filed in the 2018-2019 school year may actually be greater than those documented here because the school year was still in progress at the time of the report’s publication.

Aparna Rao, an entertainment publicist in Manhattan, is also no stranger to the Impartial Hearing Office. Phone calls from her son’s school began pouring in around the time that the boy, now seven years old, finished kindergarten. Rao and her husband ordered medical evaluations, which found that their son had delayed motor skills. “If you can’t hold a pencil and write your name and do some of those basic functions, you’re going to fall behind,” Rao said. “If you’re falling behind in kindergarten, you’re going to fall behind in first grade. It becomes a very slippery slope.”

Rushing to latch onto a foothold for her son before he slid further down the academic hill, the couple set out to create an IEP around the time their son started first grade. The Raos’ requests were minimal: occupational therapy, an Integrated Co-Teaching classroom, and counseling to help with social skills. But the school went silent. Where teachers once called repeatedly to tell Rao her son wasn’t keeping up, there was now no word on how to help him.

Three months into first grade, Rao’s phone rang again. The school had called to set a date for an IEP meeting. “It wasn’t terrible,” Rao said of the December consultation. “But nothing really got accomplished.”

Her requests had been denied, and she and the school made plans to reconvene a month later to discuss a revised IEP. January rolled around, but the school had gone dark again. When school officials finally met Rao for a second IEP meeting in February, the group still couldn’t reach a consensus. “The ball was just dropped at every juncture that we didn’t know it was being dropped,” Rao said. Frustrated, she took her case to the Impartial Hearing Office.

The case was in the works. In the meantime, it was August when Rao finally had her son’s third IEP meeting. The entire process — a “slow-moving whale,” as she puts it — had seen fall, winter, spring, and summer come and go. Rao’s son finished first grade without any of the services his parents hoped would help him get through the year. A new fall was underway, and a new school year, but it still felt like anybody’s guess if he would finally get additional support services. But the third time was the charm: Rao and the DOE finally agreed on an IEP. It took a year but she had finally defeated the whale. On Sept. 4, Rao heard more good news, this time from the Impartial Hearing Office. She had won her case, and the DOE would shell out $200,000 in compensatory education for lost time and year-late services. “There’s recourse,” Rao said of the education system. “While many people may not know their rights, that’s where the system kind of fails. It’s something you have to speak out about.”

While Alexandra Beth Neznámÿ, 28, never took up a matter with the Impartial Hearing Office like Rao did, the fellow Manhattan resident has run into roadblocks with her own child’s special education, to the point where she withdrew her son from the public education system and now homeschools him.

Her son had been enrolled in a dual-language immersion program taught in English and Mandarin. Neznámÿ herself was an assistant preschool teacher, so it didn’t take long before she picked up on differences in behavior between her son and other children his age who were in her class. “I always thought he was different,” she said. “This is his normal but it’s different than everyone else’s normal.”

The boy was evaluated and diagnosed with autism, general anxiety and a sensory processing disorder. The IEP meeting went well enough: Everyone was on the same page regarding the services the boy should receive. At one point, the case worker even leaned over to Neznámÿ and personally vowed to get the boy extra help if he didn’t do well in his first month of pre-K. Fortunately, he wouldn’t need it. He “adjusted amazingly,” Neznámÿ said.

In kindergarten, new issues bubbled to the surface. A child psychologist evaluated him but struggled to put a finger on a root cause. With or without a name, the problems would persist. “The best way to get more help was to add ADHD,” Neznámÿ said of her son’s IEP revision, even though the evaluation couldn’t say with certainty that the boy had the disorder.

Halfway through her son’s kindergarten year, Neznámÿ pulled the boy out of the public school. Having gone from a class of 10 students and two teachers in pre-K, the boy began to regress in the new classroom environment he had in kindergarten: 22 kids and one teacher. The last straw involved incidents of bullying at the hands of two separate students, one of whom was booted from the school.

Today, Neznámÿ tries to assure that her son, now seven years old, is keeping up his Mandarin in homeschool. Although his IEP grants him speech therapy, he couldn’t reap the benefits of the service for about three months because of difficulties finding a practitioner from the DOE’s list of approved service providers. Still, Neznámÿ says she is lucky to have the job flexibility — she took up her work as a pastry chef and food blogger — that allows her to homeschool her son. In addition, relatives proved a keen soundboard for her concerns, coaching her through the process. Besides her own teaching experience in the classroom, Neznámÿ’s mother is a social worker, and her aunt is an occupational therapist.

Alexandra Beth Neznámÿ now homeschools her son, pictured here, after running into a spate of issues at his public school. Image courtesy of Alexandra Beth Neznámÿ.

For many families, though, homeschooling just isn’t possible, and there are no relatives already embedded in the education system to light the way throughout the special education process. An executive assistant at a local college, Melendez noticed red flags when her daughter, now three years old, was around 18 months old. She had trouble paying attention and didn’t speak as often as her twin sister, who is neurotypical.

Melendez’s daughter was assessed and found to have developmental delays, which were grounds for her to start in Early Intervention, which she did when she was just shy of two years old. The program is the gateway to special education for the youngest group of children that the DOE encounters, offering services for children three years or younger who are not functioning at levels comparable to their peers.

Through Early Intervention, Melendez’s daughter received applied behavior analysis and speech and occupational therapies. The work paid off, and Melendez saw marked improvements in her daughter’s communication and other skills. “She loves to give me some sass,” Melendez says of her daughter today. “I can only imagine how she would be had she not been in EI.”

Shortly after joining the program, Melendez’s daughter was diagnosed with mild to moderate autism. So the IEP creation — and the barrage of questions it brings for many parents — got underway. “The IEP process is very confusing for a lay person,” Melendez said. “Because you’re brand new to this arena of special needs and getting your kid the support that they need, you don’t know the questions to ask. I don’t know if you even understand initially how to advocate for your child.”

The tug of war to determine what a child needs has many players. Parents latch onto a rope, convinced their two cents are worth the most because they spend the most time with their children. Teachers take hold of another rope, saying they observe the children in a setting most parents never see firsthand. Medical professionals enter the mix, citing expertise in the subject area. DOE employees like principals or social workers round out the bunch, drawing from previous cases they have seen and, sometimes, trying to sway the outcome based on how much the school can afford to provide extra services. “It’s a catch-22,” Melendez said. “On one end you want to make sure that they get everything that they need, on the other end, you’re not sure of what really they need. I’m not a professional, I don’t know, I’m relying on other professionals, I’m relying on other moms who navigated the process, which is why we’re in these groups.”

Melendez said her daughter’s recent IEP meeting was “cordial and professional,” barring the limited options she received for schools. When none of the three seemed to be a good fit, she did her own research, touring several schools with her daughter. The school she settled on agreed that the girl needs a smaller classroom size to receive more individualized attention and instruction. But the DOE rebuffed the recommendation. The debate will be up for discussion at her next IEP meeting in July.

For parents like Decker, Rao and Melendez, the most formidable hurdle in the special education process may have been getting the DOE to shake hands on an IEP. Yet, the trouble doesn’t always end there. Think of an IEP as a playbook — but then you’d have to say the DOE doesn’t always play by its own rules. Even after they reach a consensus and greenlight the supports laid out in the document, there is no guarantee the child will receive the full benefits provided in their IEP. In the 2017-2018 school year, the number of New York City public school special education students who received the full extent of the services laid out in their individualized assessments reached only 78.4 percent, according to the city Department of Education’s annual report on special education. During the previous academic year, the number was even lower, coming in at just 72.8 percent.

Jeannie Shaw Chambers has seen her own son be shorted of the services he was entitled to based on his IEP. When she and her wife had their son, now eight years old, in 2012, Chambers hoped he would share her love for books. To an extent, he did. He enjoyed listening to others read stories and books. But when it came time for him to read a story himself, one thing held him back from experiencing the same joy that his mother found tucked in the pages of a book: He wasn’t learning how to read.

Chambers’s son had been placed in a self-contained class, or one that is strictly for special education students, after being determined to have “other health impairments,” with no specific diagnosis. Chambers described his difficulty as a tendency to “space out.” The “other impairments” category is a catchall for disabilities that don’t fall into the other 12 designations, such as autism or visual impairment, that qualify them for special help. Chambers first noticed her son was struggling with reading when he was nearing the end of kindergarten. His inability to read as well as other children his age sent Chambers looking for answers. His teachers, the principal and other school administrators encouraged Chambers to wait it out.

That she was not willing to do. She went in search of a more immediate solution. Chambers and her wife visited their son’s school to observe him in the classroom. They quickly noticed that he was not receiving all of the services he was entitled to in his IEP. She saw her son left free to play with blocks when he was supposed to be receiving instruction. “It felt almost like they were just babysitting,” she said. “I felt like he wasn’t really getting an education in there.”

Appalled at seeing her son left to his own devices in the classroom, Chambers requested a special education evaluation from a private educational psychologist who specializes in dyslexia. The diagnosis came back as dyslexia. The next step was to modify his IEP to include additional services to help with the new diagnosis. What followed, Chambers said, was a hellish back-and-forth between her family and the DOE, in which “dismissive” district officials challenged the evaluation, saying her son was too young to be diagnosed with dyslexia.

She brought forth suggestions for services to include in her son’s individual assessment. But, after seven grueling hours in her first IEP meeting, officials brushed off her suggestions. “We got nothing that we wanted,” she said. At a second meeting, however, which she says was “much better,” Chambers and the department reached an agreement.

Today, Chambers’ son, now repeating first grade, is doing well with his reading. “He’s made more progress in the last three months than in the last two years,” she said. Although the struggle to get her son the proper help is over, it still has a hold on Chambers. The experience precipitated a dramatic change in her career goals. In the spring of 2020, she will begin working toward a bachelor’s degree in special education at Western Governors University, to prepare to give students the help that it took so long for her son to get. In spite of the lackluster education she caught in action when she observed his class, she doesn’t chalk his reading difficulties up to irresponsible teachers; the problem, she says, originates above a teacher’s pay grade, in the special education system itself. “Even if she would have wanted to do the right thing, she did not have the tools to do it,” Chambers said of her son’s teacher.

![]()

The ecosystem of actors in the special education community extends far beyond children and their parents. It has to. Parents constantly go through the rigmarole, from IEP deployment early on to an eventual legal case in which parents sued the DOE for violating the terms of their children’s IEP. In other instances, parents protest the DOE’s delays in scheduling meetings and providing services. The pattern repeats and repeats: Deny, delay, shift blame, dodge responsibility, frustrate parents, repeat.

Within the DOE, support manifests itself in different ways. Program service coordinators, for example, can help get an evaluation underway for a child. Melendez, for one, says she feels fortunate to have had a “really good” Early Intervention service coordinator who went above and beyond her responsibilities to help her daughter. “She was on top of it for what I needed,” she said. In addition, Melendez is part of a pilot program in her district that provides families with a transition coordinator to assist in the move from Early Intervention to the Committee for Preschool Special Education.

But not all parents can report having positive experiences with DOE support like Melendez did. Drew Rodriguez spotted signs that her son, now seven years old, was different in preschool and raised the concerns to his teacher, but she didn’t think anything of it. The following year, her son started having “incontrollable tantrums” surrounding his clothes, exhibiting many sensory-seeking behaviors with his socks and shoes, for example. “The shoes have to be practically cutting off his circulation,” Rodriguez said. In the classroom, he seemed to struggle with fine motor skills, gripping the whole pencil in his fist in order to write. His kindergarten teacher took note of his behavior and suggested an evaluation. Even with the teacher’s backing at last, Rodriguez says the social worker at her son’s school tried to shrug off the request, saying an evaluation probably wouldn’t yield a diagnosis anyway. Rodriguez insisted, though, and her son was evaluated that year. But, as a social worker herself, the dismissal hasn’t sat well with her. “When she discouraged me from having him evaluated, that really struck me as not right,” Rodriguez said.

Where parents feel the DOE’s supposed support system has fallen short, a network of support beyond the department has sprung up around them. Nonprofits advise the DOE on recurring issues and ways to improve the system. Lawyers specialize in special education litigation, offering their services when parents believe their child’s school failed to provide a “free and appropriate public education,” which is guaranteed under federal law. Peer advocates attend IEP meetings to ensure parents get a fair shake when giving their input on what their child should receive.

One such person is Miriam Nunberg, a special education advocate and consultant. She drew on her experience working as an assistant teacher at a Boston special education school and in the national Department of Education Office for Civil Rights. After getting involved in a working group to reform the “messed up” competitive choice style of admissions in the city, Nunberg opened a middle school herself in 2013, which adopts a garden-based curriculum like one she witnessed in action in Boston. A few years later, in 2016, she officially began her private special education consulting practice to help parents beat the “massive learning curve” ahead of them when they first become acquainted with the special education system. “They’re raising kids and they’re working — they don’t have the time to become a legal expert in this really, really complicated set of requirements,” she said. “It’s hard to do this right.”

One problem she routinely sees is the DOE failing to uphold its affirmative obligation to evaluate students with disabilities, and to do so on time. “It’s always overdue,” she said. Schools are required to offer an evaluation through the DOE if they suspect a student may have learning issues. But this often happens too late. New York state law dictates that, after parents consent to have their school-age children evaluated, the Committee on Special Education has 60 days to conduct the evaluation, determine if the child is eligible for an IEP, give a recommendation to the DOE and hold an IEP meeting. From 2013 to 2014, approximately 91.1 percent of school-age students whose parents consented to have them evaluated were actually evaluated in the state-established time frame. That figure plummeted to 71.4 percent for the following year and has remained stagnant ever since. The most recent data available, covering the time period from 2017 to 2018, shows a meager rise to 74.5 percent.

This is a key problem area identified in the 2019 DOE Compliance Assurance Plan as a mark of noncompliance with the city DOE’s obligations to students with disabilities. The city’s DOE “has not demonstrated improvement in meeting performance targets” on this indicator in the four most recent school years reviewed in the plan.

When the DOE finally does evaluate a child, options are limited. For the bulk of its evaluations, Nunberg says, the DOE oscillates between two types of tests: intelligence tests measuring IQ and achievement tests reflecting if the student is performing at grade level. But while these tests may lay out the “what” of a child’s learning abilities, they fall short of explaining the “why.” An achievement test can tell parents their child is two grade levels behind in reading, but it cannot tell them he has dyslexia. “They just do a snapshot of the kid’s profile,” Nunberg said.

Sometimes these tests are enough. For example, if the teacher or parent wants to prove that the child’s situation warrants a more in-depth evaluation, then these results can serve as a litmus test affirming the need to conduct further evaluations. No diagnosis needed, just the simple fact of deviation from expected learning.

In these cases, where further evaluations are necessary, parents may run into further roadblocks. For one, pediatricians, who sometimes shoulder the responsibility of evaluating a child after the DOE does, can sometimes give screening tests but may not always be able to carry out full evaluations. When the results come in, the evaluations are hard to decipher. “Most parents wouldn’t know what to look for if they looked at the test,” Nunberg said. This makes it harder for parents to know what services their child needs.

The outcomes of the IEP meetings can be devastating. Nunberg notes having seen an “across the board denial of services for inappropriate reasons,” noting that services may be denied to avoid siphoning away resources on already underfunded schools. She frequently learns of instances of schools denying students placements in Integrated Co-Teaching classes because they do not have the resources to pay staff for another class, for example.

PULL QUOTE LEFT: {{{{{ “It really is all about numbers when it comes back to it for a school, numbers and money,” Alpin Rezvani said. “Sometimes I think they forget everything is for the kids.” }}}}}

Karen Alves, 38, is a senior education specialist at Advocates for Children of New York, a nonprofit devoted to educational equality in the city. Alves has worked on the group’s helpline for roughly nine years, lending an ear and a hand to parents and professionals with concerns about a student’s education. She says the majority of calls she receives concern special education in public schools. The questions run the gamut, from those seeking legal representation after a suspension to those who say their children weren’t placed in the classroom settings spelled out in their IEPs.

Alves’ colleagues provide free legal representation for low-income students whose IEP conditions are not being fulfilled. “A lot of our impartial hearings involve finding an appropriate placement for the student with special needs,” Alves said. “Many times it’s because the Department of Education has somehow failed or not been able to meet that student’s needs.”

While she says no child should ever be short-shrifted of their legally required services, Alves also acknowledges the sometimes-Sisyphean responsibility the DOE has on its hands. “It’s a lot of kids, it’s a lot of students,” she said. “Sometimes teachers are definitely overwhelmed, and sometimes they don’t have the support that they need to do their jobs. I get it.”

The enormity of the task is part of the reason the nonprofit also conducts policy advocacy, working directly with the DOE to make improvements to the city’s education system. On the problem of class placement discrepancies, for example, “it still happens every year,” Alves says. “But the DOE has gotten better at trying to fix it.”

Class placements can range from inclusive models to self-contained approaches. District 75 is an example of the latter. The district serves students across the five boroughs who are deemed by the DOE to have “significant challenges,” such as emotional disturbances, major cognitive delays or multiple disabilities. Strictly intended for students with special needs, the district is the most restrictive educational environment offered in the city’s public schools.

For many people throughout the special education community, the mere mention of District 75 evokes unease. The 57 schools that make up the district carry with them a stigma: of students beyond hope, of bad treatment and worse education and even of poverty and marginalization. In the 2018-2019 school year, there were nearly 25,000 public school students in the district from kindergarten to twelfth grade. Of them, 86 percent were considered economically disadvantaged, and more of three-quarters were Latino or African-American.

In addition, a recent overhaul of the city’s special education system indicates that District 75’s self-contained approach to special education has fallen further out of favor. In the 2012-2013 school year, the city undertook reform efforts to move towards a more inclusive approach to special education in which students with disabilities share classrooms with neurotypical students. In a report on the reforms entitled “Educating All Students Well: Special Education Reform in New York City Public Schools,” Bill de Blasio, the city’s Public Advocate at the time, wrote a letter praising the efforts, which affect all 1,700 schools in the city. “For far too long, graduation rates and levels of academic achievement of students with disabilities have been falling persistently and dramatically below those of their peers,” he wrote. “While the process of reform will undoubtedly present difficulties, moving toward inclusion is in the best interest of New York City’s students with disabilities.”

One proponent of the inclusive approach to special education is Dorothy Siegel. An NYU education researcher, Siegel co-founded the ASD Nest Program that parents like Decker so desired for their children with autism.

After professionally playing clarinet early on in her career, Siegel had gotten involved in special education when she started a local district task force for it. Siegel was inspired in 1991 to spearhead the effort by a line in a Temple Grandin memoir and by her own son, who has autism. “At the time, of all the disability categories, ASD was the least successful in terms of outcomes,” she said. “So it hit me over the head, it struck me hard…If children could have such dramatically improved outcomes, then I have to do it.”

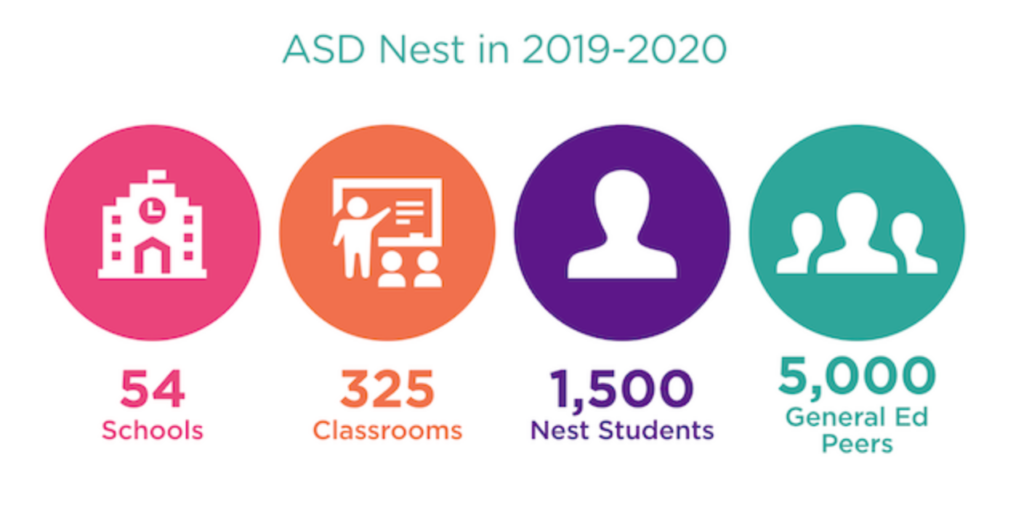

When Siegel did early pilots of the model, ASD Nest “started to spread as a funding mechanism, not as a program,” since schools saw the funding as the incentive to teach the students. It was a downfall that Siegel can only explain as being “typical Board of Ed.” Siegel pushed through this and through other pushback she received from the DOE. “I knew there was tons of resistance internally,” she said, calling the situation a moment of inertia. It was “‘We always do things this way, the way budget flows, it wasn’t going to change, it’s impossible to sustain something this different.’” More than twenty years later, in the 2019-2020 school year, the program served more than 1,500 children with autism in 54 schools across the city.

Image retrieved from NYU Steinhardt webpage on the ASD Nest Program.

But not everyone is convinced that the push towards inclusion will be very productive. In their optimism that their children “can be cured,” parents sometimes aim higher than their children can actually reach. At least, that is the assessment of Maura Roddy, a retired special education teacher for 31 years at a school in New York City’s District 75. Roddy says special education teachers are often torn between the district’s standards and parents’ demands. While the effects of inadequate teacher training are often magnified in special education classrooms, teachers may not deserve all of the blame when students’ education goes awry. “Parents are expecting their child to be like The Good Doctor,” Roddy said. “If he can’t do it, he shouldn’t be in [regular education] just because mommy wants it. Because he’s got to be able to handle the work.”

After working as a teacher, Roddy segued into the role of transition coordinator, in which she oversaw the drafting of plans to help each student transition out of high school. Having been responsible for planning what the students would do after graduation, Roddy said she had to adopt a more pragmatic approach, which sometimes meant pushing academics to the side, an idea which didn’t sit well with many parents or the district, in its push to introduce more academic standards in the classroom. “Part of our strategy was, ‘What do we want them to know when they leave here? What’s going to help them in the world?’” she said. “They want more academics and stuff like that and that’s just not realistic.”

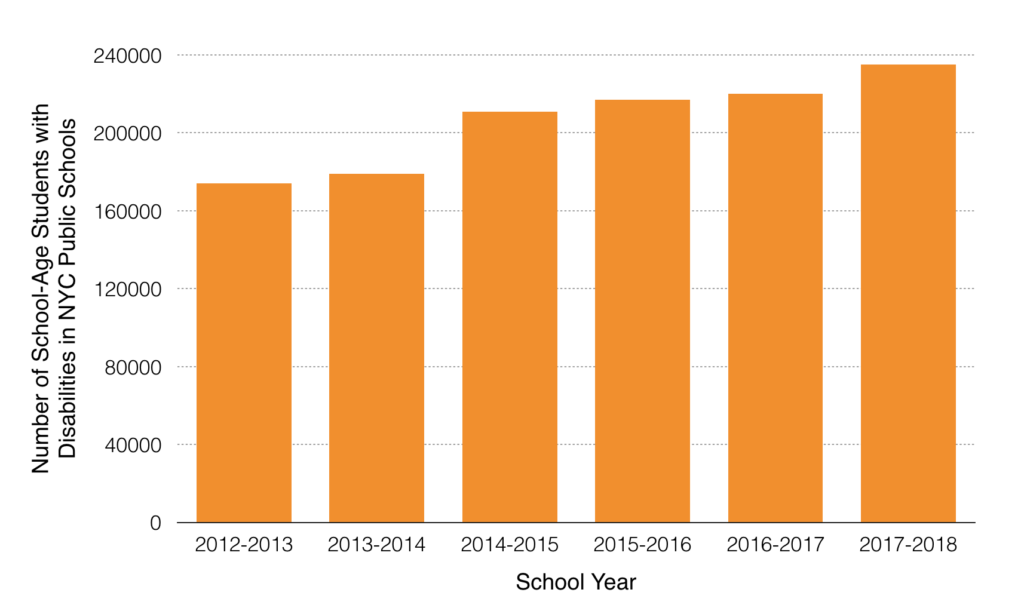

Moving forward, Roddy hopes the city will better support its teachers, many of whom are stretched razor-thin as a result of critical understaffing in spite of a clear increase in the number of children entering special education. In the 2012-2013 school year, New York City’s public schools had 174,161 school-age students with disabilities. Five years later, in the 2017-2018 school year, the number had ballooned to 235,149 students.

Graph created using figures from data.nysed.gov.

As for parents, Roddy supports advocacy for their children’s rights in the educational system but also hopes they will place higher value on teachers’ assessments of their children’s abilities. “It’s always like the parent has 100 percent control,” she said. “But the teacher is the expert.”

Crissie Bertone also has a few years as a District 75 teacher under her belt. After working as a civil rights attorney in her native Brazil, Bertone moved to New York City, where she applied for a spot in a teaching fellowship program aimed at professionals changing careers. What Bertone saw in her three years as a teacher in the district was enough to drive her right back out of the city’s education system. “It was horrendous; the kids had no services,” she said. “Everything was a big facade.”

When problems surfaced in the classroom and parents met with school officials to implement an IEP for a child, the results often didn’t live up to the document’s namesake promise of individualization. In many cases in her experience, Bertone says, “The team running the meeting does not know the child…How can you make a decision on a child you never saw?”

The IEP team is the group of people that takes part in the IEP meeting and includes parents, school psychologists and social workers, teachers, district representatives and more. But, whether it is due to overworked employees with too many cases on their plates, plain carelessness, or other reasons, some members of the team may not be adequately prepared to hold such sway over a child’s education. Because of time constraints, for example, teachers sometimes swap in and out of an IEP meeting. Teachers may have to use their own free periods to attend the meeting, which can set them back on lesson planning or other tasks for which they would otherwise use the period. If the meeting spills over into the time of a second class period, a teacher may have to swap out with another teacher to get back to her class. When parents and the DOE don’t seal the deal on the first try and must reconvene later, the composition of the IEP team can change from one IEP meeting to the next. It’s as though there is a conveyor belt winding through the meetings that lets employees pop in and out based on their availability. In either case, it grows harder to get everyone on the same page regarding the child and to tailor the IEP to his or her specific educational needs.

Dissatisfied with issues like this in the city’s DOE, Bertone went back to school, earning a certification in behavior analysis from Penn State. Newly equipped with her degree, she went back to work in the special education system, this time in Westchester. The difference was a tale of two districts. “It’s like day and night,” she said. Teachers had better training on how to work with students with special needs, and funding per student was much higher. Soon, Bertone established a clinical practice, settling into her current job as a behavior analyst and educational consultant.

Although Bertone still works in Westchester, she provides her services as a vendor, or an independent contractor, for New York City’s DOE. Her work typically includes carrying out assessments of childrens’ needs, developing behavioral protocols to help her clients’ children succeed in different environments, working with each child’s teacher to carry out the curriculum, training parents to better assist their kids and more — all things she says she wasn’t able to do as a teaching fellow. “As an employee of New York City, I was very limited and I felt very frustrated,” Bertone said. “As a vendor, that’s where I see progress.”

Speech therapist Alpin Rezvani, 36, too landed her first job in education in District 75. She began as a speech pathologist there as part of an agreement that the district would pay for her graduate program in exchange for two years of work. Once she earned her master’s degree, Rezvani worked in district schools in Harlem and the Bronx, primarily with children with autism or emotional disturbances.

While she appreciated the weekly trainings she received through the agreement, her work quickly became overshadowed by an increasing focus on maintaining records. “As time went on, I really felt like it was a lot of paperwork rather than working with the kiddos; I just found myself so bogged down with it,” she said. “I loved working with the children, and I couldn’t really do what I loved anymore.” As time wore on, the bureaucracy upkeep wasn’t the only thing about the district that rubbed her the wrong way. “My first impression was positive but then when I really got to see how administration dealt with people,” she said. “I’m not saying it’s all schools, but especially my first school, sometimes they would be super condescending and not very supportive.”

Today, Rezvani no longer works in the district. She established her private practice around 2013 when she and her husband decided to start a family. She employs about a dozen speech therapists, many of whom work in New York City. While she says she would still probably be working in the district if she was single — the appeal of job security and benefits outmatch the risks of running a private practice — she doesn’t miss what she says is the district’s money-hungry approach to education.

“It really is all about numbers when it comes back to it for a school, numbers and money,” she said. “Sometimes I think they forget everything is for the kids.”

Another agent of change in the community is Mike Rosen. The Staten Island resident, 58, officially started his own practice as a special education advocate in Dec. 2019, but he had offered his services as an advocate well before then. Prior to that, he had logged nearly two decades of work for the UPS.

Though there is no formal training required to claim the title, special education advocates can help parents navigate the dizzying labyrinth of processes that have come to define the system for many families, advising them on what services to request for their child’s specific educational needs, accompanying them to IEP meetings and more. Many enter the line of work already familiar with the special education system, having encountered it on behalf of relatives or friends. In Rosen’s case, his wife is a school psychologist for the DOE, and his daughter has an IEP for a learning disability.

Besides the ones for his daughter’s own IEP, he has sat in on almost 100 additional IEP meetings, working to root out intimidation tactics that keep kids from receiving the educational services they need. “When a parent just goes into an IEP meeting alone, that’s where it goes wrong,” he said. In these meetings, he has seen both parents and school officials lack the knowledge needed to secure the best possible outcome for a child.

Rosen hopes to see more training for school principals, who are members of the IEP team that decides the child’s education plan. “How are you going to advocate for this child knowing nothing?” he said. Still, although it is the parents, not the school, who decide whether to hire a special education advocate, Rosen says his job is to help both parties. “If they intimidate the parents, then of course I’m going to be on the parents’ side,” Rosen said. “But the parents shouldn’t be yelling at the school psychologist either.” Even after both parties have given the go-ahead on an IEP, though, Rosen still has work. IEPs are violated “all the time,” he says, with the DOE failing to hold up their end of the bargain in providing students the services named in the IEPs. “They are breaking the law,” Rosen said. “That IEP, it’s a state and federal document.”

Rosen says, half-jokingly, to his clients that they should put him out of business. The first step to this, he says, is greater knowledge among parents and greater transparency from the DOE. The end goal is for parents to become well enough informed on how to secure their child’s best education. Parents, he says, “should get the same recognition that I do.” In addition, he hopes the DOE will respect parents’ wishes even without an advocate present to play referee — to the point where no one needs Mike’s services anymore. “It’s your meeting,” Rosen likes to say to his clients. “Ultimately, you are the best advocate for your child, not me.”

Besides his day job as a special education advocate, Rosen runs a Facebook group of nearly 700 parents of children with special needs in Staten Island, District 75 or both. The description for the group reads simply, “It takes all of us to make our children’s future brighter. Mike Rosen.” In the past two years, Rosen also served as a member of the Community Education Council for District 31, the only school district in the city that covers a whole borough. Every community school district has a council made up of 11 voting members, mostly parents of students in the district, tasked with advising on educational policy, assessing the effect of school programs on students and more.

Besides the district-specific councils, there are also four citywide ones. Craig Spencer, a member of the Citywide Council for District 75, has a daughter with special needs in high school. Though it isn’t one of his formal responsibilities as a council member, his biggest priority is equipping parents with the knowledge to successfully navigate the system. This, he says, will help them make inroads towards greater accountability from the DOE. “We as advocates, we want to make sure the system works as hard as us,” Spencer said.

![]()

When Ainy Betancourt was first scoping out Grand Concourse Academy Charter School in the Bronx for her autistic 4-year-old son, she thought it was a great fit. “I was really excited for it,” she said. “When we went to the orientation, they really sold us on the whole, ‘Oh, we definitely deal with special ed and IEPs.’” But that enthusiasm wouldn’t last long. Within three months of her son’s first day of kindergarten at the school, Betancourt withdrew him from the school.

In New York City, nearly 120,000 students attend charter schools. The 2019 DOE Compliance Assurance Plan found that the city’s DOE exhibited “failure to provide special education programs and services as specified on the IEPs,” including for students of charter schools, community schools and alternative high school equivalency programs.

When her son was still in a charter school, Betancourt frequently received complaints from staff about her son’s behavior. “I was getting complaints everyday,” she said. “Everyday it was just something else.” Roughly three weeks into the school year, the school threatened to suspend her son after a classroom aide hurt his back while trying to force the boy to sit after he had refused. Betancourt convinced the school to still allow her son to receive his academic hours in math and English as laid out in his IEP. In return, she would sit with him in the class.

A special education teaching assistant herself, Betancourt quickly spotted problems in the classroom. For one, while her son’s kindergarten was an Integrated Co-Teaching class, Betancourt says the special education teacher did not arrive until the afternoon on most days because she taught a different class in the mornings. “It’s enough [doing] kindergarten regular ed,” she said. But “special ed and regular ed mixed together? They definitely need more support, and they weren’t getting that.”

Disturbed by the class’ violation of Integrated Co-Teaching requirements and its stifling effects on her son’s education, Betancourt pulled her son from the school and enrolled him in a public school.

While her son’s new school has its own flaws, Betancourt says it is significantly better than his charter school. Her son has been in public school for roughly four years now, and he is now in a class for neurotypical students with the help of a one-on-one aide. “He’s gotten so many more supports,” Betancourt said. “[It’s] much better.”

Betancourt represents a sliver of parents for whom the tables have turned and a public school special education is the solution, not the problem. For all its shortcomings, the DOE has made some strides towards progress in special education. In 2018, the city began a pilot program in three school districts, including District 75, that could help ameliorate a long-running issue. Language barriers between families and the DOE have long complicated an already-challenging process: When it comes time to sign an IEP, for example, parents who speak little or no English can struggle to grasp the parameters of the document and, thus, have a harder time ensuring their children get the services they need. In the 2018-2019 school year, nearly one in four students in District 75 were English language learners. The pilot program offers translations of IEPs into nine languages at no cost.

Things are also looking up for graduation rates. For the cohort of public school special education students who entered ninth grade between 2006 and 2007, only 31.2 percent graduated after four or five years. The students who began ninth grade between 2011 and 2012, the most recent period for which such data is available, fared better: Among their cohort, 53.5 percent graduated after four or five years.

One parent looking ahead to her child’s life beyond school is Katy Shelkowitz, 50, of Staten Island. Her son, 16-year-old Max, was diagnosed with autism around the time he turned one and began Early Intervention shortly afterwards. “You don’t believe it the first time,” Shelkowitz said. She chased after a second opinion and even a third opinion from a doctor who had Asperger’s herself. “When you go home you find horror stories on the internet,” Shelkowitz said, adding that she “spent weeks trying to prove it wrong.” Some early signs included Max’s limited vocabulary and his sensitivity to certain stimuli. One memory etched in Skelkowitz’s brain involves the time he walked into a JCC natatorium, “freaked out” about the pungent chlorine smell and flipped a stroller.

Once she came to terms with the diagnosis, Skelkowitz got to work. The DOE had offered just over five hours a week of various therapy services in the IEP meeting, flouting the doctor’s recommendations. “You’re telling me he might never talk again and you’re giving one hour of speech?” she thought. So she left voicemails and letters everyday, until she finally negotiated to 40 hours of therapy a week. “I literally have a revolving door of a seven person team coming in and out of the house every day of the week,” she said.

Like Betancourt, she found relief in an unexpected place. Her son attended a private school until he turned five, but he was aggressive there, throwing things and resisting some of his therapy. “It’s all trial and error,” she said.

Now, Max attends a public school, which Shelkowitz says is much better. But Max has become more aggressive in recent years. “I’m, like, afraid of him,” Shelkowitz said. Although students with disabilities do not age out of the public school system until they turn 21 years old, Shelkowitz has arranged for Max to join the upstate Anderson Center for Autism soon. A residential school, Anderson offers a more regimented approach that could benefit Max, as well as a smoother transition, to the school’s adult community after he turns 21 years old. The DOE will foot the bill for his time at Anderson.

Looking back on nearly two decades of deciphering the special education system, Shelkowitz says every step forward, for both she and her son, was hard-earned. Managing to retain a paraprofessional for all those years was one such triumph, as Shelkowitz stared down pressure from the DOE during their yearly IEP reviews to cut the requirement. “I fought that at every single IEP meeting since he started; what I’m worried about is the one time he needs it,” she said. “Every single thing we’ve ever gotten for Max we had to fight for,” she said. “If you don’t fight for it, you’re not getting it.”

Katy Shelkowitz plans for her son, Max, pictured here, to leave his public school within a year to attend a residential school upstate that is designed for people with autism. Image courtesy of Katy Shelkowitz.

Though she is on the opposite end of her child’s time in special education, just starting out, Melendez too has learned the special education parents’ secret code: “You really have to have that fighting spirit,” she said. “As a parent, I don’t think we realize how much power we have in this space.”

Melendez, like Shelkowitz, is already preparing for her daughter’s future, even though the three-year-old is still running around the house and asking her mother to play a toy guitar for her. “I want her to have jobs, I want her to go to school, I want all of that, so that’s what I’m planning for,” Melendez said. “But I’m also planning for if that doesn’t happen.”

One step she has taken is to start saving for her daughter to go to college. “My expectations are definitely managed, but I’m not going to sit here and be like ‘I don’t think she’s ever going to leave the house,’” she said. “I anticipate that she’s gonna go to high school, have all the drama of being in high school, go to college. I don’t know if she’ll stay in the dorm. But I anticipate all of that for her.”![]()